Archive

Seeking asylum – Day One

Feb 25th, 2015 | Immigration, Refugee Community, Rejection, VF Opinion | Comment

“I am so scared. I haven’t slept for three days. I am afraid Immigration will arrest me and put me in CIC [detention centre]. I don’t want to be deported because I can’t go back to my country,” sighed a 40 year Srilankan mother who secured informal refuge in Hong Kong through the domestic worker scheme – not an unusual practice for women escaping domestic, gender, ethnic or political violence in her country.

Vision First accompanied Ibrahim of the Refugee Union on an escort mission to Immigration Skyline Tower, in Kowloon Bay, where new asylum seekers are required to report to the General Investigation Section prior to lodging non-refoulement claims. The process is nerve-racking for persons who overstayed visas, or might have entered illegally, and must then surrender to immigration authorities to establish a protection status and void being arrested by police in the street.

“Without the Refugee Union I was too scared to surrender. I didn’t reported for two years to Immigration after I was terminated. I didn’t know what to do. I am afraid the police will arrest me,” remarked an undocumented Indonesian woman whose passport was retained by an agency for failing to settle exorbitant fees relating to her dismissal. “I better be a refugee in Hong Kong than go back. I owe loansharks 82 million Rupiah. They threatened to kill me if I don’t pay back with interest!”

“Before taking them to Kowloon Bay,” explained Ibrahim, “we register new cases and email Immigration with details and copies of documents. Only after receiving replies I bring them here to make sure new [claimants] are not arrested. Officers play tricks with those who come alone, like refusing to accept claims for some reason, or demanding documents they cannot produce. But if we go with them they will not arrest you.”

The lavish decor of this prestigious commercial building contrasts starkly with the grim tasks faced by dozens of hopefuls who commence their asylum ordeal at Skyline Tower with understandable trepidation. They start queuing up every morning at 8am on the ground floor, among officer workers accustomed to their presence, knowing that by 1030 an unofficial daily quota is closed and latecomers are gruffly waved away.

On 24 February we spoke with citizens from Gambia, Pakistan, Nepal, Tanzania, Srilanka, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Nigeria and Indonesia who were unwilling to leave Hong Kong and understood that seeking asylum was the only pathway to remain legally for as long as they could. “I need more time. I have problems back home that make it dangerous for me. I don’t want to live in Hong Kong, but for now I must stay until I figure it out!” explained an African who had lived three years in China.

The lifts of Skyline Tower keep releasing a mix of colourful characters on the 5th floor landing. Confused and befuddled overstayers emerged with eyes darting left and right searching for clues. They were visibly nervous and probably uninformed about an asylum adventure that equally ill-informed peers might have recommended. At this stage, a credible and independent information service could possibly guide hundreds towards wiser and more practical choices.

Immigration officers at the only counter are likely challenged by a ten-fold surge in asylum claims: from 491 cases in 2013, to 4634 between March and December 2014. The authorities might find it hard to explain the unprecedented surge despite policies designed to avoid ‘creating a magnet effect which could have serious implications on the sustainability of our current support systems and on our immigration control.’ The time might have come to completely overhaul the asylum process.

The cultural clash at the General Investigation counter is absolute: on one side of the window is a strained officer fielding questions in English and Chinese (resident friends seem to prefer the latter); while on the other side an anxious bunch presses for attention without the benefit of a number system. It becomes clear why the meek and less assertive are bounced back week after week.

Here is the gate that should bear the infernal sign: “Abandon hope all ye who enter here!” it is here that passports are sequestered, sometimes not be returned for years, and options reduced. For a few hours the hopeful pace anxiously the 5th floor lobby where neither a bench nor stool welcomes the weary. Then the system starts to divide: the fortunate are asked to photocopy documents and take a photo (average cost 70$), while the unfortunate are given a notice to return in a week or two.

There is a sense of relief among those who received a numbered ticket to queue up for the photo booth in room 504. They appreciate that they were not detained and in the afternoon they will obtain a Recognizance Form 8 issued by Hong Kong Immigration to overstayers seeking asylum. At this moment, the hopeful care less about the zero percent acceptance rate and more about the opportunity to remain in town for a few more months or years.

After Immigration officially releases them on recognizance, having established a breach of the original conditions of entry – thus criminalizing them as overstayers – asylum seekers may proceed to the 9th floor to lodge a USM claim. The process is simple: they submit a now standard form that circulated since January 2013 (it was first distributed by Vision First) and request a photocopy with a date stamp. A few weeks later Immigration will follow up with a request for written significations of claims and eventually offer an appointment to record fingerprints and photos.

Three times a week Ibrahim guides Refugee Union members to Kowloon Bay. He jokes about an officer complaining, “Don’t keep bringing people here, you make us busy”. Another officer once asked him for ID and wasn’t satisfied when he produced a RU membership card. Ibrahim was unfazed, “If you don’t like it, arrest me and call the police. They will confirm that they registered the Refugee Union to help all these people who are waiting here and wonder the streets without papers.”

For the avoidance of doubt, you are not welcome, refugees are told

Feb 23rd, 2015 | Immigration, VF Opinion | Comment

The rebels incinerated the home of a father of five, killed three family members, and brutally tortured and left him for dead. When news spread that he was still alive, arrest warrants circulated and, a dead man walking, the father fled alone to China with the assistance of a consular friend. His wife and children hid in the bush where his eldest son died. Almost two years after seeking asylum in Hong Kong, Immigration Department accepted his claim as substantiated.

Another victim of persecution, a parent of two children, sought the protection of Hong Kong Government in mid-2014 and was recognized a refugee less than a year later with the support of exhaustive documentary proof. Between 3 March 2014, when the Unified Screening Mechanism was launched and 12 February 2015, there were 5 substantiated cases out of 826 claims, maintaining Hong Kong’s effective zero percent acceptance rate (0.61%).

Setting aside vexing doubts about the other 821 claimants denied protection, Vision First is deeply concerned about the harsh and inhospitable treatment of successful claimants. They are in one breath notified a potentially life-changing decision and also informally told they are not welcomed to integrate and reconstruct a new life in Hong Kong.

Despite the promise of not deporting them into harm’s way, claimants are made acutely aware that the prohibition from working stays while they remain confined to the same inadequate welfare provisions they experienced as asylum seekers. Protection (from refoulement) does not come with the right to make a living in Hong Kong.

The Notices of Decisions clearly express the authorities’ position on reluctantly granting temporary asylum until alternative solutions are identified to rid the city of the annoyance of refugees. Claimants are informed that “in the circumstances, you will not be returned to [your country] for the time being”.

Then cases are “passed to the UNHCR for consideration should (you) be recognized as refugees under its mandate and … resettled to a third country as appropriate”. It seems that asylum policies in Hong Kong haven’t evolved from reliance on the United Nations to conveniently sweep away local problems with minimal expense and hassle.

The Notice of Decision warns that, “the making of removal order against you would not be precluded”, i.e. stopped, as “the Immigration Department may consider whether there is any special country other than (your homeland) to which you may return. If any such specific country is identified, you may be removed there.”

Further, the Notices of Decision issued by the Immigration Department states, “if you wish to leave Hong Kong at your own initiative, you may do so notwithstanding your substantiated non-refoulement claims. Please however be reminded that your non-refoulement claims will be treated as withdrawn and will not be re-opened if you leave Hong Kong.”

Finally, another paragraph in the disheartening notices warns, “For the avoidance of doubt, please be also reminded that a person will not be treated as ordinarily resident in Hong Kong … during any period in which he or she remains in Hong Kong only by virtue of a non-refoulement claim, including the period when his or hers non-refoulement claim is substantiated.”

The analysis of such protection documents reveals five warnings from Immigration: 1) we won’t send you back for now; 2) you are not welcome so get the UNHCR to resettle you elsewhere; 3) you are under a removal order and could be deported to another country; 4) you can’t work and won’t receive adequate welfare, so you can volunteer to leave; 5) if you are stuck here for years be aware that you are not treated as ordinarily resident and won’t be allowed citizenship.

As if the above were not depressing enough, the inauspicious Notices conclude with a final warning, “Please also note that your substantiated non-refoulement claim may be reviewed should there be any changes of circumstances and other reasons for considering revocation.”

Hong Kong Immigration’s notices granting international protection to distraught refugees conclude with the word: REVOCATION. It might reflect the spirit in which the Immigration Department reluctantly grants protection following a series of court judgments warning that, “the courts will on judicial review subject the [Immigration] determination to rigorous examination and anxious scrutiny to ensure that the required high standards of fairness have been met.”

I came to Hong Kong to save my life not work

Feb 17th, 2015 | Housing, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Welfare | Comment

I am a 30 year old South Asian who escaped the breakdown of law and order in a country where corruption protects the powerful who commit crimes with no fear of arrest or prosecution in court. It is meaningless for HK Immigration to claim, “You failed to report the incident to the police [in your country]”, because protection is guaranteed to the highest bidder, not to victims.

One night in 2010 I was smuggled on a speedboat from China to Hong Kong with ten other people. We were very lucky because the next day a powerful typhoon struck and the dangerous crossing could have been deadly. I was very scared at sea on a flimsy fishing boat in pitch darkness. At one point we were hit by a huge wave and we thought we would die.

The smugglers landed us on the coast and told us to walk into the mountains to find the road. They didn’t come with us and we got lost walking at night. For seven days we roamed the mountains in Sai Kung Country Park. We had no food and drank from the streams we crossed. We were relieved when the police arrested us because we were desperately hungry and afraid we wouldn’t make it.

For five years I have been suffering as a refugee. The rent and food we receive is not enough. I have lived three years in the slums, the only place I can rent a room for 1500$. I used to work to pay for a village room, but I suffered a serious injury in the container port. A wave struck the container barge we were offloading and a cargo chain detached and snapped my right arm.

I have heard about two refugees who died under falling containers. I doubt there were any inquiries into their deaths or safety procedures were reviewed. Bosses give refugees dangerous jobs because they know we cannot complain and they won’t have to pay for damages if we get hurt. I did not come to Hong Kong to die, but to live. I risked my life coming here and also working to survive.

Last week my ISS caseworker (name withheld) told me not to protest. He said that a big officer would visit the slums and I should not join the demonstration for safe housing. I stayed in my hut and waited. The big officer did not come. I think ISS tried to block the protest because they don’t want us to talk about our suffering. ISS tell me to find a legal room for 1500$, but they know it is impossible.

I only get some food and 1500$ rent from ISS. In five years they gave me nothing, then last week they gave me a green blanket. I waited five winters for one blanket! Everything I use I collected from nearby garbage dumps where I go on Saturday nights after residents dump old things. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have clothes to wear, a bed to sleep on, a fridge to store food and a stove to cook.

I am not an economic migrant. I came to Hong Kong to save my life, not work or be a beggar.

Refugees in Hong Kong see little improvement from new screening system

Feb 16th, 2015 | Immigration, Media | Comment

AFP photographer visits the slums

Feb 13th, 2015 | Housing, Immigration, Media | Comment

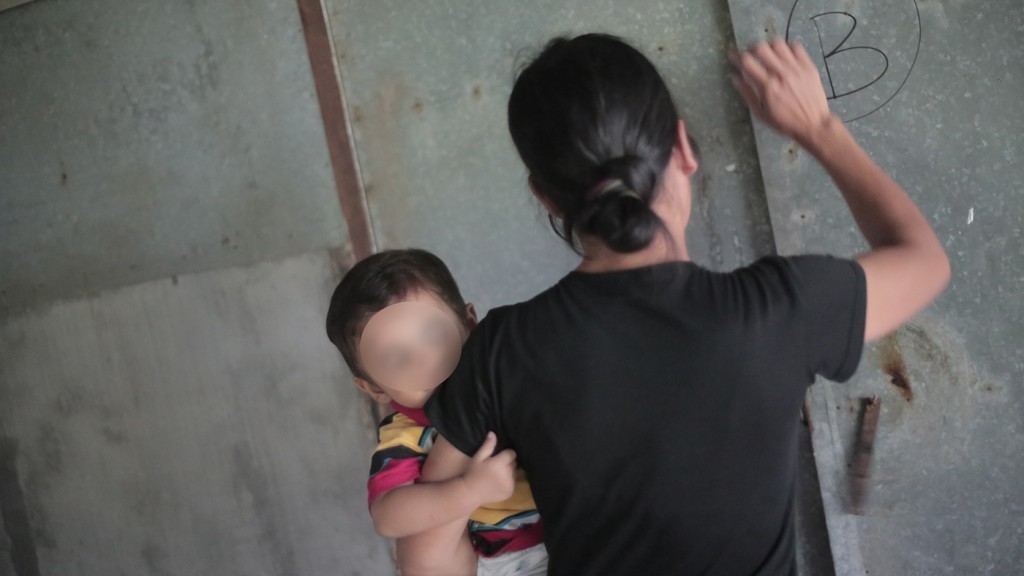

Following the death of a refugee in the Hong Kong slums, AFP went on assignment with the Refugee Union. The shameful treatment of vulnerable asylum seekers was captured by an expert lens for the world to witness. Over a day we visited five notorious slums and met refugees who on average waited already five years for a decision on their claims without receiving a reply. They wait patiently in total destitution as those responsible turn a blind eye to their plight.

The material used to partition slum rooms are advertising billboards that might have been discarded after some fancy show at luxury shopping mall. It is striking that amid the city’s unbridled affluence there are human beings suffering under government care without proper accommodation. These living conditions tarnish the reputation of Hong Kong as an international financial centre where every person ought to be treated with respect, irrespective of immigration status.

The refugees welcomed us inside their shacks where, they explained, every item was recovered from garbage pits including electric stoves and flat-panel TVs. They spoke about the dynamics of survival in a metropolis, where coping without work is harsher than most people imagine. Despite such odds, refugees preserve great dignity which was masterfully captured by the photographer.

From all accounts, it might be the twilight of refugee slums in Hong Kong and the Refugee Union was grateful for the coverage this reprehensible policy is getting. “Show the world how they treat us,” exclaimed Afzaal from Pakistan, “We are not animals to lock in a farm shed. One night a snake bit my leg inside my hut. I had no idea if it was poisoned. We are scared of electricity, flooding, fires and the police banging our doors in the middle of the night. We are refugees, not criminals.”

Hong Kong needs sustainable solutions in refugee policy

Feb 11th, 2015 | Housing, Immigration, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

Rose is a refugee mother living in the slums. She was distressed speaking to us, “My officer no give money to the landlord from 1 February. The officer said ‘Danger the place. You find another room. Rent money stopped paying already.’ Room outside very expensive. I must find another room, but I don’t have money. What can I do?”

Rose lamented, “If I leave and stay in ISS shelter where I put my property? I have double-bed, full kitchen and many bags of clothes for me, my husband and son. Landlord said we must pay cash for February rent or we cannot leave. [In her slum] landlord is asking 30 refugees to pay cash this month. He threaten everyone to pay before we leave.”

In September 2006 a South Asian refugee was settled in a pig farm by ISS-HK. His caseworker approved the arrangement with the landlord without inspecting the shack as Vision First reported in August 2013. A few months later ISS-HK relocated him to a guesthouse. Yesterday he was alarmed, “ISS said I must leave by Thursday. The cheapest room is 3000$ so where I find a room for 1500$. Where do I go? I am very afraid.”

Aziz is a vocal campaigner for better housing assistance for refugees evicted from the slums. He is unable to find a cheap enough room for himself and his wife. He reports, “ISS didn’t pay our rent in January and February. But ISS continue to pay for electricity and water. Why they don’t give more money to rent [better accommodation] than give it to the landlord? Officers from Lands Department tell to me this lot must all be demolished and turned into farmland.”

Richard is an African refugee settled by ISS-HK in a guesthouse 14 months ago when he was unable to secure a 1500$ room. He reports, “My caseworker said I must leave on Monday, but I refuse. Where I go? Do they want me to live in the street? ISS put me in a guesthouse when I was homeless a year ago. Today house prices are much higher and they still want me to find a room for the old price. What are they thinking? Refugees are not animals to kick outside …”

An SWD spokesperson responded to our bog “Housing crisis expanding to guesthouses” with this comment, “Thank you for your email of 6 February 2015 regarding the claimants living in guest houses arranged by ISS. We are looking into the matter and ISS has been alerted about it.” Something is not right. Isn’t the contractor implementing policies dictated by the government? Isn’t shifting responsibility to underlings cowardly incompetent to say the least?

Facts lead us to believe that the authorities caused the present housing crisis by a combination of (un)foreseen ramifications and unforgiving market forces. The time has come for the government to rethink their approach and the following constraints should be evaluated:

- refugees are not a temporary ‘problem’ to be fixed with residual humanitarian assistance;

- a work ban disempowers refugees from actively participating in problem solving;

- unrealistic rent assistance prices refugees out of basic rooms, exposes them to incarceration for working illegally while enriching unscrupulous citizens;

- after years of negligence the refugee slums are targeted for closure following Lucky’s death;

- lodging refugees in guesthouses for about 7000$ a month was ill-advised;

- the escalating housing crisis is a threat to social stability and public security that demands longterm, sustainable and reality-based solutions.

I gave birth to a son from another man

Feb 3rd, 2015 | Crime, Immigration, Personal Experiences | Comment

Good evening Vision First. I got my new Immigration paper and I have to report with my son every two weeks at CIC detention. My officer said he will proceed the papers for the Education Bureau for my son’s school. Thank you so much for giving us strength to insist on our rights and to have hope to fight every day. We owe you a lot.

I am one of hundreds of failed domestic workers who cannot return to their country because they have big problems. We are refugees because we must stay in Hong Kong to save our lives. I come from a village in the Philippines where I was married and had a child. When I had problems with my husband I came to work in Hong Kong.

My husband will never forgive that I separated from him and I give birth to a child from another man. Nobody can change his mind to take revenge on me. His mother is very close friend to council district and municipal authority members. He and his brother are working for the municipal government. His position is TASK FORCE and they have big connection with our mayor.

They are doing violence to their enemies because they have power. They always deny they are doing this, but they do it again and again. In the Philippines it’s big danger to be a witness and hard to ask the police to help if nothing bad happens first. Also it is hard to hide in another place, because every village report new people and it is hard to hide from my husband’s friends.

He will know that I am somewhere. I must protect my son all the time because he wants to kill us both. My country is not safe and not easy to ask to anyone for help. I am scared to face him and I am more scared what will happen to me and my son’s life.

Since I married him I feel not happy for his being strict and jealous. But I try to work it out with my family. When I gave birth to my first child, I was wishing he will change, but no, he get worse. One night he took a knife and kept stabbing my pillow and searching my house. And then he bought a gun. When he knew I am seeking help from my family, he tell them he never respect them and kept making trouble with them.

One day he tried to rebuke my niece until they hit each other and he got hurt. He bring that problem to the court and until now that problem is not closed, because we don’t have lawyer so we just using the court lawyer. That moment I decided to separate from him slowly. But I was scared because in everyday of my life in the Philippines he kept on following and trapping me everywhere. Every time I kept screaming, even in my work place where he disturb my boss.

But one night that I will never forget he stopped me in the street corner. He was there waiting for me and he pull me … I try to be brave, but when I see his gun pointed at me … I got hurt. I knew that he can kill me anytime. I complained many times to the police and the council but they could not do anything.

That was three years ago when I decided to work abroad to escape from him. But he took my child from my parents and threatened me, so I have no choice but to send him some money. He took opportunity again to disturb me and he took all the details of where I am working and even make me frightened in Hong Kong. He took my son and never let me see him again.

In Hong Kong I got three employers but felt no good with any employer, it’s because I still feel fear and anger. When I got boyfriend and had my second son, it seemed to change my feelings. I told my family what happened and suddenly my husband went to their house and kept shouting that he know all about me even my son. He is still angry and still not stop to search for me and my son. He told my parents he has a photo of my son and he will kill us both. He still wants to take revenge so I am scared.

Mandated refugees and screened-in torture claimants have no right to work in Hong Kong

Jan 27th, 2015 | Immigration, Legal, Media | Comment

Are dependent visas reasonably denied?

Jan 27th, 2015 | Crime, Immigration, Legal, VF Opinion | Comment

After seeking asylum in Hong Kong, one of the first things refugees learn from peers is that they will never be allowed to integrate and earn a living (including successful non-refoulement claimants) unless they marry a resident and successfully obtain a dependent visa – which requires withdrawing protection claims before the sticker is affixed to a passport.

Immigration guidelines indicate that dependent visas generally take three months to process, although refugees experience a different treatment that, when successful, is likely to take two years and otherwise drags on for many years with litigation (which doesn’t come free) rising as the only option to break the stalemate, if official obduracy can be described as such.

A refugee blogger recently described immigration strategies as perceived by his community, “They know that certain people will find a way that is convenient for the government – though unfair for refugees – like marriage, moving to another country, smuggling out and closing asylum claims through so-called ‘voluntary departures’.”

The stigmatization of individuals who sought sanctuary in Asia’s World City is so profound that even years of love with local citizens cannot wash it away. Not even when beautiful children are living proof that marriages are real and a genuine family exists behind the paperwork that, in the mind of immigration officers, might have thrown a monkey wrench into removal proceedings.

A pattern emerges when scores of dependent visas are denied or delayed for applicants who were so unfortunate as to seek asylum before falling in love. It is unrealistic to expect that authorities publish statistics on failed application, which in our view should include applications stalled by ‘non decisions’ for over one year. The data would speak volumes about the bias treatment of refugee spouses.

It is regrettable that Immigration consistently fails applicants who committed mild offenses such as working, despite work being absolutely necessary for refugees to make ends meet since they do not receive adequate welfare assistance and belong to ethnic groups that are largely shunned by charities as being less deserving of their limited resources.

Working illegally is a matter of survival for most refugees, but a criminal conviction will jeopardize the fate of a family – including the future of resident children – even if a struggling refugee was arrested years before for selling bootlegged software or fake leather bags to keep a roof over his head or supplement meager food rations. Where is the fairness of laws that constrain pathways of survival only to mercilessly penalize those with no alternative but to stray?

A few examples illustrate the predicament faced by dozens of refugees:

Case one: a refugee since 2005, married in 2013 and was denied a dependent visa for reason of a life-time deportation order triggered by a 2007 offense “to export goods to which a forged trademark was applied” [NB: copy goods] at a time before he knew about refugee welfare assistance.

Case two: a refugee since 2005, married in 2011 and has a son. He was convicted of working, though he pleaded not guilty as he was visiting a friend at his place of employment. He was nonetheless convicted to four months and marked as ‘persona non grata’.

Case three: a long time refugee since 2002 married in 2008 and has a son. This family has been waiting for a dependent visa for 6 years. Arrested for false representation to an immigration officers after arriving in Hong Kong with a dodgy passport, he was served a deportation order that he gets suspended every year by the office of the Chief Executive. He has no chance of being granted a visa until said order is quashed.

Vision First takes the view that refugees must not be punished for struggling to survive in a hostile environment arguably designed to push them into criminality. On Sunday a refugee was arrested for being in possession of 5 mobile phone chargers (worth 300$) which he is accused of intending to trade, presumably to support his wife and child. Wouldn’t police resources be better allocated pursuing more substantial criminal activity?

It is further a travesty of justice that resident spouses and children are denied a legitimate future. There is a need for a moratorium on immigration rules the stringent application of which will never persuade fathers to abandon their loved ones.