Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment?

Apr 20th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

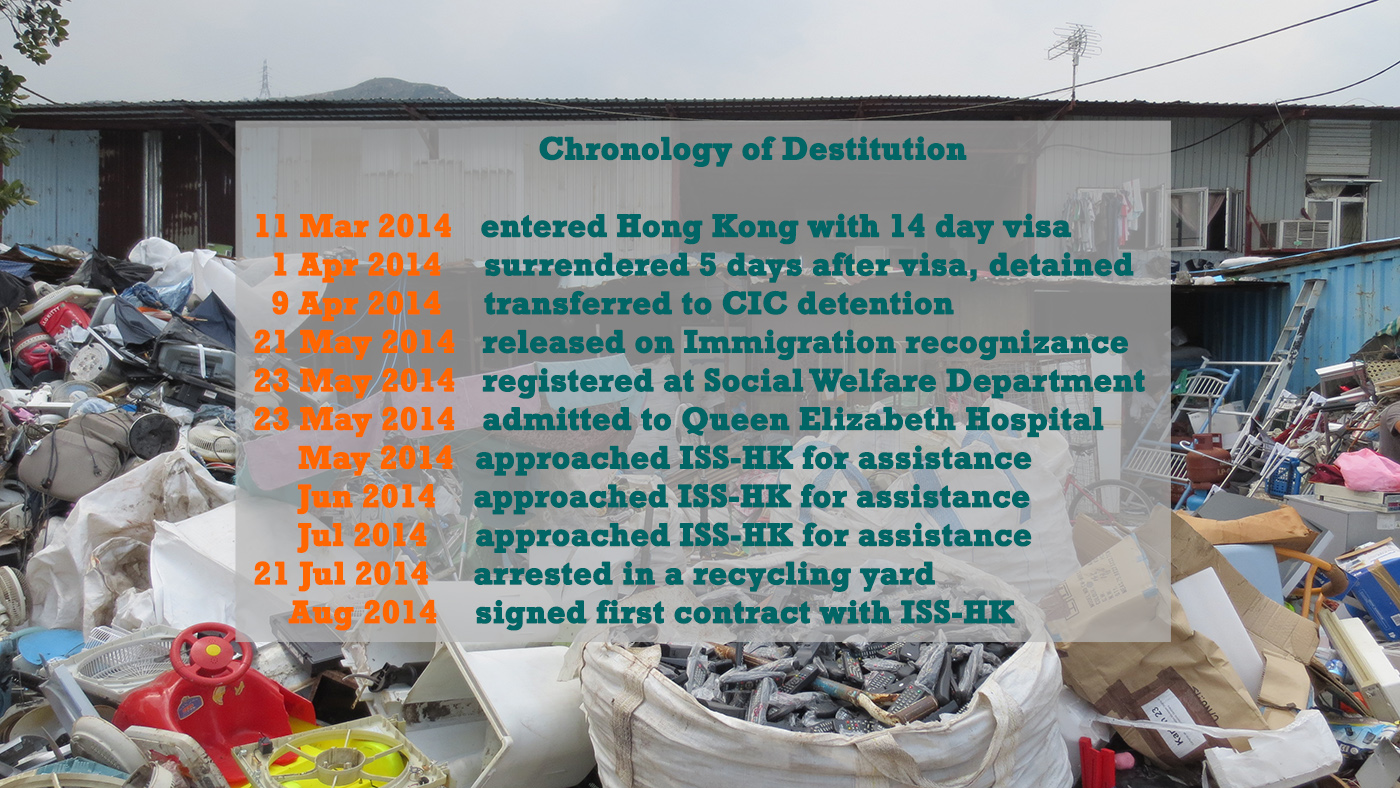

Called to the stand in Shatin Magistracy, Mohammed faced charges of breaching conditions of stay by taking up employment unlawfully. With the assistance of a Hindi interpreter, the despairing 50 year-old listened carefully before entering a plea – NOT GUILTY!

Asylum seekers are most commonly tarred with one brush. Public opinion is almost unanimous in accusing them of beating a path to our city to fraudulently drink in its riches by abusing welfare assistance, or toiling in the underground economy. Obfuscating the truth, the authorities regularly promote to the inattentive a rejection rate of 99.9% as evidence that only 1 in 1000 claims is meritorious.

The government remains unyielding and is adamant that the asylum mechanism offers genuine claimants a fair chance. No explanation is given about cases that have been pending for years often stretching to a decade. At the other end of the spectrum are recent arrivals who presumably didn’t expect to suffer like beggars after lodging protection claims with the Hong Kong Government.

Everything was better in Mohammed’s life before he took refuge in our city. If he didn’t face danger, he wouldn’t have left behind a supportive wife and adult children, abandoning a comfortable home and a thriving family business. At half a century of age, he hardly fits the stereotype of an adventurer seeking a better life in a developed country where illegal work might support remittances home.

One night, a few months after being released from Immigration detention, Mohammed regained consciousness in a ward at Queen Elizabeth Hospital. “I didn’t know how I got there. I was feeling ill that morning as I hadn’t had anything to eat and I was exhausted by sleeping outside week after week. The nurse told me that I had hit my head when I collapsed in the street. An ambulance was called and I was admitted to hospital for three days until I recovered.”

Holding back tears, he finds it hard to continue, “Those were the only three days when I ate properly since I was released from CIC. The nurses gave me extra food to make me stronger. For several months before I only ate what shops donated to me in Chung King Mansions. It was never enough. I lost a lot of weight and was often sick. I was worried when discharged from hospital as I knew I would be hungry.”

Mohammed reported that he had registered at the Social Welfare Department and had been referred to ISS-HK, but nobody called him for months. He forgets how long it was because several months passed in a blur of destitution, begging for handouts, sleeping in the streets, falling sick and depressed and always struggling with hunger. As if life couldn’t get more distressing, it did.

One Ramadan afternoon before the Zuhr prayers, he was accosted by a faithful at the Kowloon mosque who, presumably noticing his grime state, inquired about his condition. Mohammed explained that he was a refugee and had long run out of money and support. The well-wisher showed concern and with the enticement of a ‘breaking fast meal’ invited him on a trip in a private car to a recycling yard in Lok Ma Chau. The arrangement did not raise the suspicions of a newcomer in an international city.

Beggars can’t be choosers and nothing seemed out of the ordinary for hungry Mohammed about Muslim faithful offering desperately needed support in the name of Zakat – charity being one of the five pillars of Islam and a special obligation during Ramadan. Nobody suspected that police commandos were concealed in nearby bushes cocking machine guns to raid the isolated yard.

Around 3:30pm, before Mohammed enjoyed a single morsel of food, armed police burst inside. In the ensuing chaos, the panic-stricken refugee dove inside a wrecked car hugging the rusty floor until he was dragged out by the collar of his jacket two hours later, sweaty and confused. The fact that he was hiding from enforcement agents was subsequently put forward as evidence of his guilt.

Mohammed stands accused of working illegally. The police took photos of those arrested after the raid, not when they were allegedly working. The threadbare clothes of a homeless existence were put forward as work clothes, though Mohammed had arrived an hour earlier and his hands were clean.

It is certainly possible that Mohammed is lying and had accepted an offer for work at a time of acute desperation. Perhaps Mohammed is afraid of admitting the truth for fear of being jailed for 15 months for working illegally. Perhaps it wasn’t the first time he went to that yard and the police had failed to take such photo. But he claims to be innocent. And this arrest consequently raises more questions than answers.

How much of a crime is it to steal bread when you are hungry? How are refugees expected to survive for weeks and months before receiving welfare? For that matter, refugees are trapped between inadequate assistance and cope without breaking the law. Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment? In some jurisdiction offenders may be found innocent when authorities use deception to make arrests. Shouldn’t the courts take note of contextual evidence?

Residual welfare is formulated to entrap refugees

Apr 15th, 2015 | Crime, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

In pre-industrial, agrarian society the needs of the vulnerable were generally met by family, kinship provisions, neighbourhood, informal support networks, religious institution and the charity of the rich based on normative values of empathy, mutual help, locality ties and religious beliefs. The state offered no institutional assistance.

In modern times, these informal arrangements were admirably taken over by the state in the interest of “those who are not capable without help and support of standing on their own feet as fully independent or self-directing members of the community”. It was understood that “welfare addresses social needs accepted as essential to the well-being of a society. It focuses on personal and social problems, both existing and potential.” (HK Gov 1965 + 1991 White Papers).

Nonetheless, with 1.5 million citizens living in poverty, and thousands more struggling to afford three square meals a day, the Hong Kong welfare model is often considered an embarrassment. The administration falls short of fully mobilizing its considerable resources to alleviate the emotional and economic suffering of its most vulnerable citizens.

In reality, scholars tend to see local welfare as a residual system. That is welfare that only partly ameliorates the failures of the market economy, precisely because the privileges of the rich in society should not be undermined by a burdening tax system that is claimed would inevitably become needed were more services needed by larger numbers of welfare claimants.

After decades neglecting refugees, the government provided welfare in 2006. But the authorities persistently reiterate the service is “to prevent destitution while not creating a magnet effect which may have serious implications for the sustainability of our current support systems and for our immigration control.” In other words, this is another form of residual welfare.

But here is the catch. Uprooted from family, kinship and locality ties, refugees in Hong Kong are displaced and deficiently assisted by support networks, institutional services and charitable organizations. The assistance levels provided by the government condemn them to dire poverty that is compounded by the denial of work rights and 15 months imprisonment for those arrested working.

As opposed to a solidarity model based on principles of mutual responsibility, a residual welfare model offers a partial safety net confined to those who are unable to manage otherwise, with the assumption that they are able to locate further sources of assistance on their own. This notion then suggests that 10,000 refugees in Hong Kong ought to supplement inadequate government assistance through hand-outs from family, countrymen, neighbours, religious institutions and NGOs … or by working illegally.

Policies directed against the poor have to do with the government abdicating its duty to alleviate distress and poverty, as much as with crafting a hostile environment in which an undesirable foreign class adapts by resorting to all sorts of social tricks and risking arrest for doing something illegal because they have no choice. A case in point is a refugee who already has 5 convictions for theft. He candidly explains, “I steal baby formula because easy to sell. If police arrest me I go prison 2 to 3 months. If I am arrested working I will go prison for 2 years because of prior convictions.”

The expectation of self-reliance from refugees who frequently don’t know a soul in town is absurd. They report the absurdity of the residual welfare system through suggestions commonly made by their case workers:

– “You must wait 2 to 3 months before we start the assistance.”

– “We cannot help you. You must find the money yourself.”

– “You should ask some NGO to pay for or donate what you need.”

– “You should ask your friends to help you pay for it.”

– “You should find some church to assist you.”

– “This is not our problem. You must manage by yourself.”

How many refugees enter illegally from China?

Apr 13th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion | Comment

“Our experience is that walls do not work … Walls can sometimes divert movement, but will not solve the problem”, said the UNHCR chief Mr. Guterres about the doubling of asylum seekers in Europe in 2014.

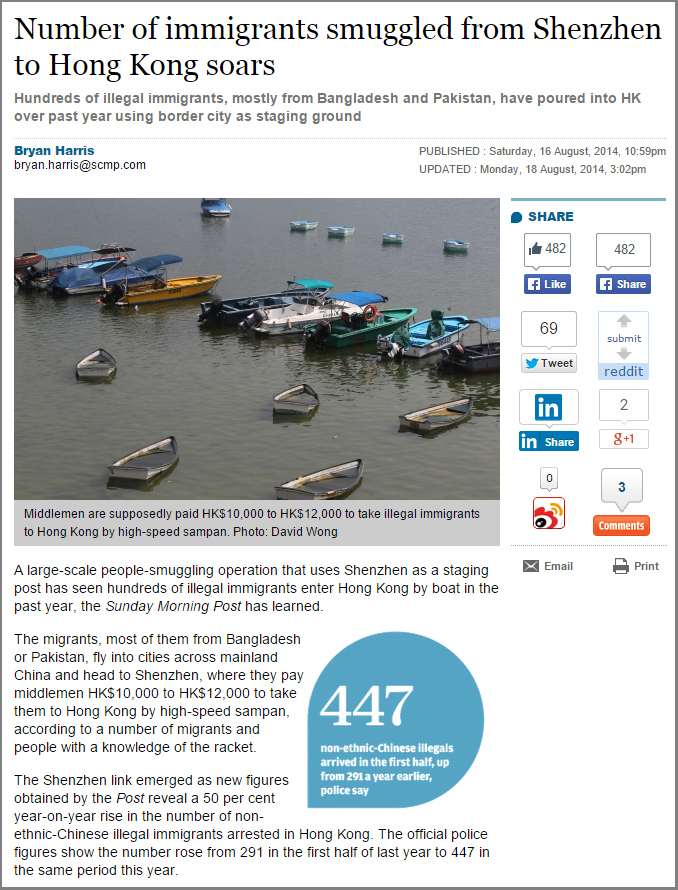

Hong Kong experienced a surge in the number of people claiming asylum, with 4,634 new cases lodged between March and December last year. Are these new asylum seekers also new arrivals? Have they been absconding for years and only recently came to know of this avenue of protection?

The CIA World Factbook puts Hong Kong’s land border at 30 km and its maritime border at 733 km, most of which is hard to penetrate undetected. We can only guess, but what is hardly a conjecture is that the controlled entrance points at the airport and land crossings are not the only passages into Hong Kong.

At a time when the authorities are targeting undesirable arrivals at the airport, nothing is said about the considerable number of refugees who enter illegally through other ways – some for the second or third time. It appears that the border with China is rather porous and, for the right price, the trip can be arranged with few hassles and no delay. The choices are various: through the fence, over the hills and by speedboats, known colloquially as ‘ferries’.

From many accounts collected by Vision First over the years, entering without a visa is not a matter of difficulty, but unsurprisingly only a question of money. In 2009 the going rate was 4,000 HK$, while today refugees are charged 12,000 to 15,000 HK$ per person.

Why is it so? Who is involved and who profits from this trade? Certainly it does not seem unreasonable, if the government is really worried about a trend that sees ever more requests for protection, to control what is now an extremely porous border. Or is it not a priority?

Here is the narrative of a refugee who recently arrived from Shenzhen that indicates the ease with which arrangements and journeys are made:

“I couldn’t get a visa with my same name so that is why I had to get illegal entry to Hong Kong. We applied for visa for China. It is not easy. I checked online. I checked with tourist agents. We made a tourist package and China sent us the information. We paid 238 USD per person in our group and they issued a letter that we took to the embassy in (our country).”

“Then we bought one-way air tickets to Guangzhou and stayed at a hotel booked online. The second day we took a train to Shenzhen … We didn’t get a stamp on our passport so we didn’t know how long we could stay in China. We waited there.”

“I asked [people] if there is any way to go from there to Hong Kong. A man gave me his mobile number. I used to talk to him every day. He kept telling me, ‘It is not ready. When it is ready I will let you know.’ He asked for 13,500 HKD each person … Every day I called him and asked when we can leave. He said the sea is dangerous, the cops can come there, so you must wait.”

“Almost one month later he suddenly called, ‘Today you must get ready’ … At 6pm we checked out of the hotel. We called a taxi. I called a Chinese guy who told the taxi driver where to go. I don’t know the location where the guy was waiting for us. He saw us and said, ‘You follow me’. I had never seen him before. We walked … then we stopped in a very dark place. He showed us a place on the water.”

“He told us to go sit (on the shore). There were stones in the shallow water and our feet got wet. Later several rowing boats arrived and took us. They rowed for a while and stopped under some trees, along the seashore. We waited longer. Then one of them took a torch and flicked the light a few times. Suddenly a motorboat appeared from the dark …”

“It was an outboard boat made of wood, about 3m long. It had a big engine. I was very scared. In my life it was the first time I had this experience. I was holding on and did not know what would happen. The driver said, ‘Keep still. Don’t move. Head down. Police there.’ He drove very fast …”

“Suddenly I saw my SIM card activated to Smartone, then I knew we were in Hong Kong. I ask him to stop us there as we were afraid and wanted to get off the boat. But he said, ‘No. Just sit there!’ He stopped further up by a small slope. He walked up and asked us to follow him. He called another man who was 20 meters away.”

“I feel that the border between China and Hong Kong is easy to cross. All the time I was praying in China on the bed because even my friends said it is not easy. I was afraid of crossing the sea, but these people made it very easy. Perhaps I was lucky because others say it is very dangerous …”

The other side of the domestic work-refugee nexus

Apr 10th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community, VF Opinion | Comment

There are two sides to the issue of foreign domestic workers falling pregnant and losing their jobs – one is local, the other overseas. On the home front, TVB recently reported on the plight of thousands of maids whose lives were disrupted by pregnancies that are not formulated into policies and, in some cases, are not respected by employers as workers’ rights.

There are some 320,000 foreign domestic helpers (FDH) who account for around 3 per cent of the Hong Kong population. The infamous case of Erwiana symbolised the risks of serious human and labour rights violation by devious employers who might treat maids as disposable slaves. By seemingly failing to enforce the law, the government is not making their plight easier.

Maternity protection is clearly a major concern for hundreds of thousands of female workers in prime child-bearing age. The Employment Ordinance is crystal clear: maids are eligible to 10 weeks’ paid maternity leave (after 40 weeks employment) and the dismissal of a pregnant worker is an offense. An employer who contravenes the provision is liable to prosecution and a fine of HK$ 100,000. But how many employers were successfully prosecuted?

The grim side of this story is that hundreds of pregnant maids seek asylum after being unjustly terminated, or falling out of employment The fear of departing Hong Kong should not be oversimplified. The fear matrix may include complex factors: income loss, illegal work, local partners, prior relationships, support networks, loan sharks, debt bondage, ostracization, religious prohibitions, family shame, customary expectations, racial discrimination and the threat of honour killing.

Contrary to popular belief, any person who overstays in Hong Kong may lodge a protection claim which ought to be approached on the premise that it is genuine until it is proven that it cannot be substantiated. Consequently no adverse inferences may be drawn against ex-maids (pregnant or not) since they might have legitimate claims and several have been recognized as refugees.

Our blog “Understanding the domestic work-refugee nexus” explained that maids are predictably drawn into the asylum sphere for several reasons. A crucial one is that they are not just workers, but are also women who endeavour to foster human relations in a society that diminishes their social worth and dehumanizes their femininity. It is natural that maids and refugees date because both communities are shunned by residents and are often deemed lesser human beings.

The distribution of thousands of boxes of Pampers (and condoms) at Vision First testifies to an escalating problem that the authorities are advised not to underestimate. The big picture is as predictable as it is problematic. Short of sterilization, Immigration has no way of curbing the sexual activity of 320,000 mostly female maids and 10,000 mostly male refugees who find comfort in each other’s arms. Is it surprising that these two communities meet and mingle?

Under the existing scheme, the government offers pregnant maids few choices but to return home under impoverished, unsafe circumstances, or seek asylum. Refugee fathers have little to offer their new families without work rights and adequate welfare assistance. The immigration status of the children follows that of the parents: if neither is a permanent resident, then the children are overstayers under the family’s or a parent’s claim.

The fear matrix becomes crucial. Once the asylum process is concluded, mothers ponder the pros and cons of returning home: Is the fear greater than the prospect of an immiserated existence? Is the danger of returning substantial, or could alternatives be explored given time? Nobody is under any illusion about the zero percent acceptance rate, but the variables are many and timing is key, because it is easier to return with a toddler than an infant. It would be advisable to allow mothers to work again rather than compel them to seek asylum as the only available pathway.

The government is concerned about the escalating cost (640 million HKD according to this report) of the asylum scheme. Priority should thus be given to formulating viable alternatives. Hong Kong society cannot enjoy the privilege of (underpaid) domestic workers without making provisions for natural consequences. We should not turn a blind eye to thousands of women whose rights are violated by policies that fail to envision maternity and its ramifications locally and overseas. Again Hong Kong is attempting to have its cake and eat it.

Refugees suffer a contaminated service mindset

Apr 3rd, 2015 | Food, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

The big picture is one of government policies crafted to punish individuals for seeking asylum and encourage their departure. The justifications of ‘avoiding the creation of a magnet effect’ and ‘preventing the opening of flood-gates’ are cunningly raised to stoke fears and draw support for the current treatment that borders on social cleansing.

Propaganda brainwashes the minds and pollutes the hearts of gullible citizens who unwittingly (or not) are imperceptivity conditioned to homogenize refugees’ narratives and motives into an amalgam rich with xenophobia and poor in human rights. This reduces refugees to an annoying inconvenience for otherwise comfortable residents, some of whom might make a living in the asylum field.

On 2 April 2015, two refugee women reported recent experiences with service providers who used a malicious tool to abuse and deprive them of respect – words. Both were women, both were mothers, both were gentle and soft-spoken and unlikely to kick up a storm in protest, which conditions demand we listen carefully to their complaints.

A South Asian mother of one, complained to her case worker (name withheld) about the quality of food collections. She expressed her views politely, requesting improved provisions that were not always the cheapest available. The mother lamented that foodstuff for children had little nutritional value and lacked variety. She said she was told: “Why you complain? It is free! You should be happy with what you get for nothing.”

An African mother of three, reported to her case worker that some food was contaminated. A Ziploc bag containing a box of macaroni was produced as evidence. The package was home to two undesirable creatures, one dead and one alive – cockroaches! The case worker presumably handled the issue with the grocery shop concerned. At the next food collection the mother had another unpleasant surprise. Instead of an apology, she received threats. She said she was told: “Why you give me trouble? Did I give you trouble? So now you want trouble for your family?”

Refugees need not be treated as high-value customers at some luxury shop. Yet they are customers nonetheless. Case workers earn salaries to perform a welfare job on behalf of the Hong Kong people. They need not be grateful, but they ought to be respectful. It is hoped more emphasis will be placed on professionalism that might build understanding and ultimately improve services.

The shopkeepers and owners of the seven grocery shops appointed by ISS-HK run profitable businesses. They are not doing charity by any means. Presumably they earn a decent profit on every item sold, including the contaminated box of macaroni. The outcome might have been different if the package had been given to the Food and Environmental Hygeine Department (FEHD), which Vision First advises refugees to approach in such cases.

Why should refugees be intimidated when raising legitimate complaints? Why should a mother be targeted for reprisal for speaking out?

No solution in sight for refugee housing crisis constructed by SWD

Mar 25th, 2015 | Housing, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

“My home burned in the Tim Sum Tsuen fire. One month already I just sleep here and there. No one helps me to find a home. I really don’t know what to do. Actually there are many homes, but for $1500 where I can find one? When I try to ask ISS officer, they say only, “I will try to find room for you”. But when will they find it? Also one day a friend told me there was a home near the area of Tim Sum Tsuen. I was very happy, but it was too expensive at $4000. So I tried (to share with) two people, but ISS saying again, “You put $1000. You pay home balance yourself.” (The 2 person allowance is $3000). How I can pay? I have no work, no salary. Still I try to ask ISS, “OK you cut my food money by $500 and my friend’s too.” However again ISS officer said, “I can’t. So sorry,” and closed the phone.” (edited for clarity)

Vision First received this message from a refugee woman who lived in the slum with the rusty gate in Tim Sum Tsuen before it burned down in a blaze on 25 February 2015.

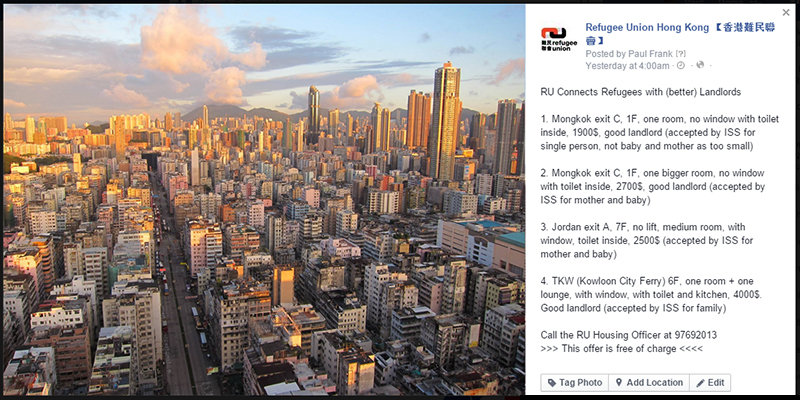

On 24 March 2015, the Refugee Union posted on Facebook rooms for 1900$, 2500$, 2700$ and 4000$, ranging from coffin-size with no window, to a one-bedroom suite. These are current market prices. Guesthouse rooms are no longer provided for homeless refugees, forcing many to share beds or sleep on the floor in the rooms of others. Contrary to what the authorities claim, very few rent subdivided rooms for 1500$ and such old contracts are probably coming to an end. What alternatives are there for refugees?

A new arrival slept on the sofa at Vision First for several months, “I want to get my own place, but the cheapest room is 1900$. How can I pay the 400$ difference every month? Will the government increase the rent allowance?” As a computer engineer he could get a job, but he is afraid of being arrested and being incarcerated for 15 months.

A couple from Sudan wrestled with the exorbitant prices of the cheapest flats for months, “ISS will only pay 3000$ and the smallest place we found was 3800$. I can get a medical certificate to raise my allowance to 2000$, but what about other refugees? Do they have to be sick to get more?”

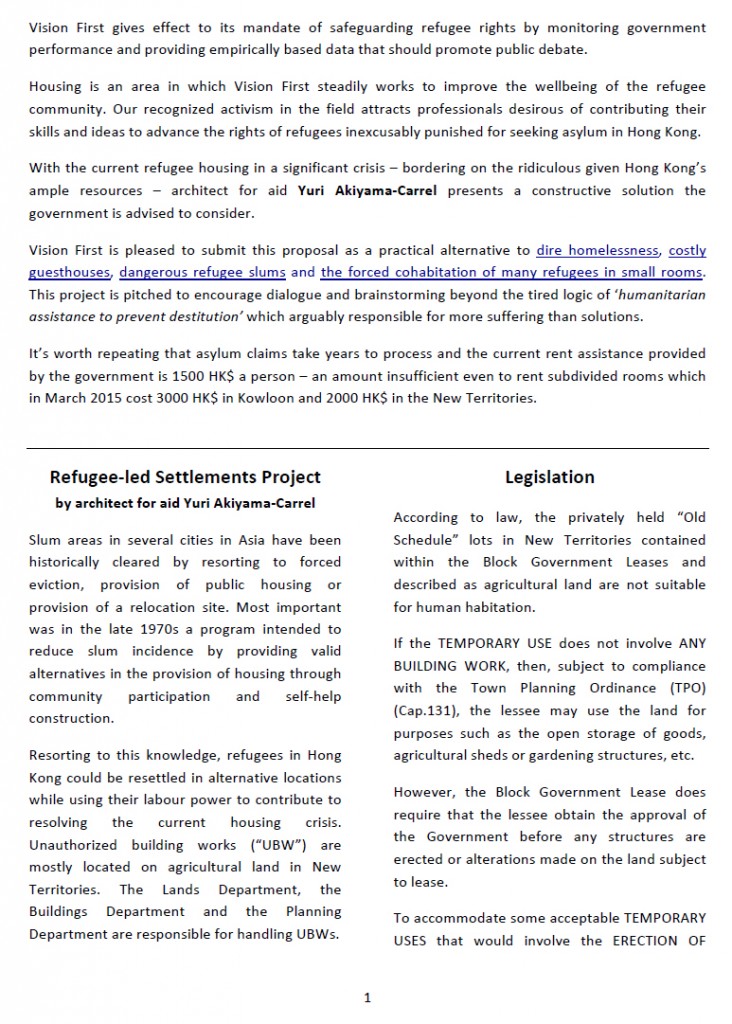

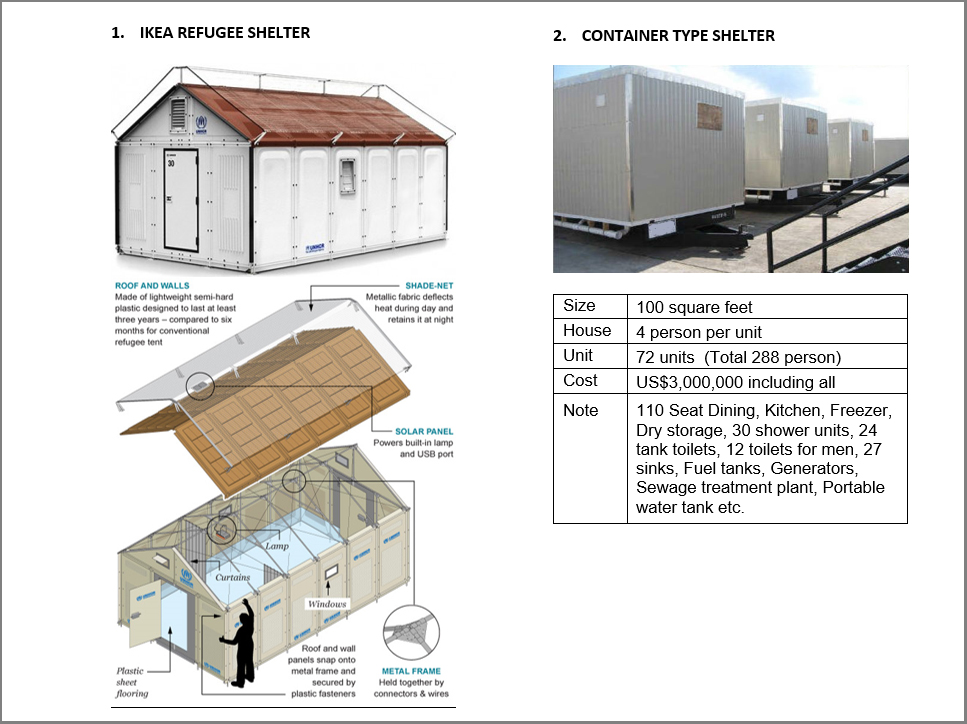

Since refugees are destitute, the suggestion made by the Refugee Union to the Social Welfare Department is worth exploring: “We request the government, through its appointed officers in SWD, find suitable living locations for refugees and take part in the signing of rental agreements, creating a relationship between SWD and the landlord to ensure safe and practical living conditions are met.” Alternatively, Vision First advanced the proposal of a concerned volunteer who introduced the case for cheap temporary housing – “Refugee-led Settlements Project”

The plight of the disposed tarnishes the reputation of Hong Kong that hoards a surplus of US$ 8.2 billion while its most vulnerable citizens suffer. From cage people to struggling elderly and street-sleepers, the administration has little compassion for the downtrodden. It’s a bleak existence for those eking out a living at the bottom of society and, without work rights, refugees are the hardest hit. A genuine humanitarian consideration is regrettably lacking.

Open letter to Hong Kong Immigration on Right to Life claims

Mar 23rd, 2015 | Immigration, Legal, VF Opinion | Comment

Hong Kong asylum system is in a shambles

Mar 20th, 2015 | Food, Housing, Immigration, Legal, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

The Unified Screening Mechanism may as well be said to have failed in keeping up with its promise of protection, remarked a senior lawyer at a Vision First meeting this month. He was of the opinion that the administration mismanaged the process to such an extent that fair-minded observers would not consider it a success, if not for rejecting 99.9% of asylum claims.

The big picture is alarming. USM was expected to finally process claimants, whose numbers hovered around 5000 for years. But in 2014 the number doubled to 10,000, with new claims lodged at more than 300 per month. This surge surprised the administration that expects a considerable rise in screening costs, welfare assistance and the publicly funded legal scheme.

The backlog of claims is expected to increase further as refugees becomes familiar with the “Right to life claim” (BOR 2) which requires that asylum bids be also assessed on grounds relating to Article 2 of the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance, which is binding on the Immigration Department.

From documentation acquired by Vision First and freely available on the LegCo website, it seems that rather than reviewing an asylum system, that seems to neither protect nor uphold refugee rights, the administration is considering fast-tracking screenings, affecting legal safeguards. However, placing departmental expediency and completion targets ahead of obligatory “high standards of fairness” will pave the way for extensive judicial reviews, warned the HKBA.

If the administration’s approach to screening and determination is cause for alarm, the welfare side is of little consolation. It should be pointed out that hundreds, if not thousands of claimants have been in limbo for years without adequate welfare or employment rights. Such unfair treatment inflicted unjustified hardship on already vulnerable persons who hoped to find sanctuary in Hong Kong.

Instead of protection, refugees experience rejection through countless difficulties that hamper their daily existence. It takes months to obtain assistance, during which time new arrivals are often left hungry and homeless, fending for themselves in the streets. “We signed the contract with ISS but cannot find a place for 3000$. Without a room ISS only provide dried food like biscuits, instant noodles and canned food!” lamented an African couple who has slept on a sofa-bed at Vision First for several weeks.

The mismanagement of food rations continues despite refugees vociferously protesting for more than a year. There might be a widening rift between the SWD and ISS-HK that exposes a communication problem, to put it gently, relating to millions of dollars in food allowances that failed to reach the plates of destitute and hungry refugees. “Where is the remaining money” questioned Cable TV.

The 69 refugee slums exposed by Vision First are emblematic of the faltering asylum system. As a matter of fairness and humanity, it is reasonable to expect that the slums be wound down gradually without mass evictions that cause preventable homelessness. To the contrary, the same indifference to the wellbeing of refugees manifested in the establishment of slums, is blatantly obvious in their abrupt closure without offering basic, functional and safe accommodation.

A distraught refugee recently made homeless exclaimed, “I waited seven years for Immigration to [determine] my case. Still no answer. Now I have no place to stay and nowhere I can rent for 1500$. Hong Kong wants all refugees to go away! If we could go to another country we would leave … but how?”