Blaze incinerates a refugee slum favored by ISS-HK

Feb 27th, 2015 | Crime, Housing, Personal Experiences, Welfare | Comment

Nobody was prepared to witness the devastation wrought by last night blaze on “The slum with the rusty gate” which Vision First brought to the attention of the authorities in October 2013 for reasons including a considerable fire hazard. In 2015 acts of God seem arranged to shut down refugee slums which (un)concerned government departments have been reluctant to dismantle.

Walking over the soaked remains of incinerated shacks which offered no sprinklers, fire extinguishers or fire hydrants (fire services laid hoses for trucks several hundred meters away), refugees observed it was a miracle nobody had died. “If the fire happened two hours later when everyone was asleep and the doors were locked, something worse would have happened for sure” noted Mumtaz, whose wife dashed out with their 2.5 month-old daughter, without a chance to grab her purse.

Burned remains, perforated tin sheets and bent metal beams reveal a conflagration that a crew of 165 firefighters with 35 fire engines could not contained till every shacks had been consumed by the raging fire. Eight fire trucks were dispatched to the nearest access road several hundred meters from Lot 2153 in Demarcation District 124, where ISS-HK currently sheltered 7 refugees, including children and a pregnant woman.

Unconfirmed reports indicate that the fire might have started in Francesca’s hut, constructed in a pigsty with metal sheets, plywood and no brick walls for sturdiness and protection. The hut was cluttered with a jumble salvaged from dumps, typical of refugee who scavenge to obtain everything they need. Francesca was known to cook on an electric stove, rumoured to have started the fire, which she brought home from a rubbish dump with no functionality assurance.

Ms. Mumtaz describes her escape, “I was cleaning the house and the door was open. I heard two loud bang noises. I looked and saw [Francesca’s] hut was burning very bad. We use cooking gas [large 27Kg. cylinders] and I was very scared of explosions. I was so afraid …. I grabbed the baby and ran away in my nightgown. I didn’t have time to take my other documents, just the her birth certificate.”

Yusna lives in a nearby refugee slum, “This is the third time I see fire like this. Every night I sleep with my daughter and I am afraid. Two years ago it happened in Hung Shui Kiu and ISS moved me to another slum. Then there was another fire and I moved here. But we are not safe like this. These houses burn very very fast. There is no way but run away.”

Arif of the Refugee Union commented, “It is the second fire in ISS slums in one month. They are lucky nobody died last night. God is telling them that the slums are dangerous and next time there will be dead people. These refugees lost everything: clothes, furniture, appliances, nothing left. It takes a family more than a year to collect everything they need from garbage. What can they do now?”

Mr. Mumtaz lived in this slum for 3.5 years with rent paid by ISS-HK from the government purse to a purported landlord. The address displayed on his ISS-HK Agreement on Provision of Assistance signed on 12 February 2015 is: Rm B3, No. 12 Tin Sum Sun Tsuen, Yuen Long.

There is a minor variation from the address shown in hisISS-HK Agreement signed on 13 September 2013. It is significant that the Lands Department officially identifies this location as Lot 2153 in Demarcation District 124 in Tin Sam San Tsuen. What justifies the considerable discrepancy?

Fire burns through a refugee slum, again

Feb 26th, 2015 | Crime, Housing, Refugee Community, Welfare | Comment

On 25 February 2015 at 10:30pm alarming SMS circulated, “Good evening, I want to give information. There is fire in the Chung Uk Tsuen [slums] near the home of Yusna. Precisely in the house of Refugee Union Francesca … two houses burnt to a crisp … She was rushed to the hospital because she was limp and panic.”

A month after a fire took the life of Sri Lankan refugee Lucky, another blaze raged through a compound near Tuen Mun, in an area with the highest concentration of refugee slums supported by ISS-HK with government funds. An intricate maze of narrow paths intersect agricultural lots where rusty, ramshackle ruins of pigsties and chicken sheds are turned into illegal dwellings.

It is reported that a gas cylinder blew up in the shack of a resident Pakistani, starting a blaze that engulfed the compound familiar to Vision First as “The slum with the rusty gate”, reported on 4 October 2013. At the time we noted that residents lived in and maintained better abodes than penniless refugees who cannot afford repairs and whose ISS-HK contracts displayed fake addresses.

Police cordoned off the area to facilitate the work of dozens of firemen and medics who worked frantically till 2pm. Preliminary information indicates that the blaze broke out shortly after 9pm and took almost four hours to extinguish presumably due to a lack of fire hydrants and vehicular access, combined with challenging nighttime conditions.

Assuming that all slum dwellers escaped unscathed, the complex erection of several shacks on two storeys and the unregulated storage of gas cylinders probably increased the danger faced by rescuers. This blaze didn’t only threaten the life and property of refugees, but also of residents who apparently don’t enjoy the building standards and fire safety regulations which ought to protect everyone by law.

Vision First is concerned about Francesca and her two year-old son Ismaeel who lived in one of the huts reported to have burned to ashes. In 2010 Francesca fled to Hong Kong with a well-founded fear for her life. She was not a domestic worker. The awful living conditions she endured in the slum bore witness to the severity of the domestic violence that compelled her to leave five children behind.

Last night Francesca was taken by ambulance to hospital in a state of shock. She often complained about her dangerous hut, but had no money to relocate. Her home flooded in the rain, backed in the sun and seemed poised to collapse under its own weight. Hers was one of the worst shacks documented and a crying shame for caseworkers who permitted a mother and baby to live there.

An act of God draws attention again to the slums where indigent people – in this case residents and refugees – live in hazard conditions that the authorities chose to ignore despite their very existing challenging rules and regulations. An activist observed, “The rule of law is bent. But since no one complaints, it is fine. Let business go unimpeded, since business is all that matters in Hong Kong.”

Seeking asylum – Day One

Feb 25th, 2015 | Immigration, Refugee Community, Rejection, VF Opinion | Comment

“I am so scared. I haven’t slept for three days. I am afraid Immigration will arrest me and put me in CIC [detention centre]. I don’t want to be deported because I can’t go back to my country,” sighed a 40 year Srilankan mother who secured informal refuge in Hong Kong through the domestic worker scheme – not an unusual practice for women escaping domestic, gender, ethnic or political violence in her country.

Vision First accompanied Ibrahim of the Refugee Union on an escort mission to Immigration Skyline Tower, in Kowloon Bay, where new asylum seekers are required to report to the General Investigation Section prior to lodging non-refoulement claims. The process is nerve-racking for persons who overstayed visas, or might have entered illegally, and must then surrender to immigration authorities to establish a protection status and void being arrested by police in the street.

“Without the Refugee Union I was too scared to surrender. I didn’t reported for two years to Immigration after I was terminated. I didn’t know what to do. I am afraid the police will arrest me,” remarked an undocumented Indonesian woman whose passport was retained by an agency for failing to settle exorbitant fees relating to her dismissal. “I better be a refugee in Hong Kong than go back. I owe loansharks 82 million Rupiah. They threatened to kill me if I don’t pay back with interest!”

“Before taking them to Kowloon Bay,” explained Ibrahim, “we register new cases and email Immigration with details and copies of documents. Only after receiving replies I bring them here to make sure new [claimants] are not arrested. Officers play tricks with those who come alone, like refusing to accept claims for some reason, or demanding documents they cannot produce. But if we go with them they will not arrest you.”

The lavish decor of this prestigious commercial building contrasts starkly with the grim tasks faced by dozens of hopefuls who commence their asylum ordeal at Skyline Tower with understandable trepidation. They start queuing up every morning at 8am on the ground floor, among officer workers accustomed to their presence, knowing that by 1030 an unofficial daily quota is closed and latecomers are gruffly waved away.

On 24 February we spoke with citizens from Gambia, Pakistan, Nepal, Tanzania, Srilanka, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Nigeria and Indonesia who were unwilling to leave Hong Kong and understood that seeking asylum was the only pathway to remain legally for as long as they could. “I need more time. I have problems back home that make it dangerous for me. I don’t want to live in Hong Kong, but for now I must stay until I figure it out!” explained an African who had lived three years in China.

The lifts of Skyline Tower keep releasing a mix of colourful characters on the 5th floor landing. Confused and befuddled overstayers emerged with eyes darting left and right searching for clues. They were visibly nervous and probably uninformed about an asylum adventure that equally ill-informed peers might have recommended. At this stage, a credible and independent information service could possibly guide hundreds towards wiser and more practical choices.

Immigration officers at the only counter are likely challenged by a ten-fold surge in asylum claims: from 491 cases in 2013, to 4634 between March and December 2014. The authorities might find it hard to explain the unprecedented surge despite policies designed to avoid ‘creating a magnet effect which could have serious implications on the sustainability of our current support systems and on our immigration control.’ The time might have come to completely overhaul the asylum process.

The cultural clash at the General Investigation counter is absolute: on one side of the window is a strained officer fielding questions in English and Chinese (resident friends seem to prefer the latter); while on the other side an anxious bunch presses for attention without the benefit of a number system. It becomes clear why the meek and less assertive are bounced back week after week.

Here is the gate that should bear the infernal sign: “Abandon hope all ye who enter here!” it is here that passports are sequestered, sometimes not be returned for years, and options reduced. For a few hours the hopeful pace anxiously the 5th floor lobby where neither a bench nor stool welcomes the weary. Then the system starts to divide: the fortunate are asked to photocopy documents and take a photo (average cost 70$), while the unfortunate are given a notice to return in a week or two.

There is a sense of relief among those who received a numbered ticket to queue up for the photo booth in room 504. They appreciate that they were not detained and in the afternoon they will obtain a Recognizance Form 8 issued by Hong Kong Immigration to overstayers seeking asylum. At this moment, the hopeful care less about the zero percent acceptance rate and more about the opportunity to remain in town for a few more months or years.

After Immigration officially releases them on recognizance, having established a breach of the original conditions of entry – thus criminalizing them as overstayers – asylum seekers may proceed to the 9th floor to lodge a USM claim. The process is simple: they submit a now standard form that circulated since January 2013 (it was first distributed by Vision First) and request a photocopy with a date stamp. A few weeks later Immigration will follow up with a request for written significations of claims and eventually offer an appointment to record fingerprints and photos.

Three times a week Ibrahim guides Refugee Union members to Kowloon Bay. He jokes about an officer complaining, “Don’t keep bringing people here, you make us busy”. Another officer once asked him for ID and wasn’t satisfied when he produced a RU membership card. Ibrahim was unfazed, “If you don’t like it, arrest me and call the police. They will confirm that they registered the Refugee Union to help all these people who are waiting here and wonder the streets without papers.”

RU letter to Security Bureau on full assistance for students

Feb 24th, 2015 | Refugee Community, Welfare | Comment

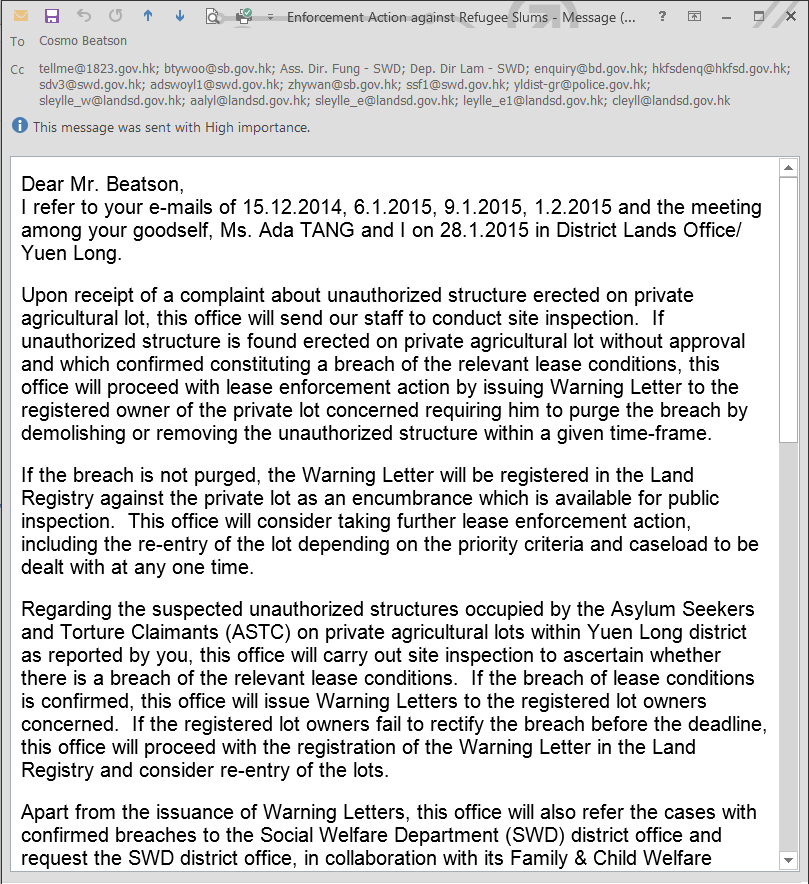

RU proposes caseworkers sign leases

Feb 24th, 2015 | Housing, Refugee Community, Welfare | Comment

The Refugee Union floated a new idea as reported by a recent post on Facebook. The SWD or ISS-HK should sign the lease agreements with landlords to house refugees. The proposal makes perfect sense because refugees:

- Are entirely and passively dependent on welfare;

- Did not determine the rent assistance of 1500$;

- Have no savings or income to handle economic transactions;

- Are prohibited from working under threat of 15-22 months jail;

- Have no bargaining power with landlords and agents.

The Hong Kong Government ensures that refugees suffer destitution with the aim of avoiding the creation of a ‘magnet effect’ that would encourage others to seek asylum in the city. As such, the authorities are responsible for their lodging, food, clothing and medical services of this group.

Given that refugees often scramble for cash to purchase necessities such as cooking gas and shoes, it is unreasonable to expect penniless people to sign a 12 to 24 month tenancy agreement for residences that, in today’s market, typically cost more than 2500$ when assisted with only 1500$.

No wonder estate agents and landlords are loath to rent properties to refugees. Property owners expect to be paid rent monthly and don’t appreciate chasing tenants for payments which might be indefinitely delayed due to lack of income. Who in his right mind would rent his property to an unemployed individual who has no savings and work rights?

By deciding that refugees should not work, the government denied the entire group participation in solving the problems relating to their livelihood. By doing so, the authorities effectively reduced them to ‘children of the state’, who can do nothing more than beg from charities and well-wishers. If that is the nature of seeking asylum in Hong Kong, then refugees are 100% dependent on the state.

There are other advantages to having caseworkers secure and sign lease agreements. First, they would experience the stress of flat hunting with a laughable 1500$ budget. Second, they would appreciate negotiations with wary agents and landlords unsure who will foot the bill. Third, they might become advocates for a better housing policy as they clash against the inadequacy of current arrangements.

It seems that refugees have had enough of the housing games and want caseworkers to handle the impossible task of renting rooms for a 1500$ budget and dealing with the complications that arise from forced cohabitation when several individuals share a tiny room. The question is how will refugees compel caseworkers to step into this minefield?

Oscar goes to Snowden documentary ‘Citizenfour’ with Hong Kong in starring role

Feb 23rd, 2015 | Media | Comment

For the avoidance of doubt, you are not welcome, refugees are told

Feb 23rd, 2015 | Immigration, VF Opinion | Comment

The rebels incinerated the home of a father of five, killed three family members, and brutally tortured and left him for dead. When news spread that he was still alive, arrest warrants circulated and, a dead man walking, the father fled alone to China with the assistance of a consular friend. His wife and children hid in the bush where his eldest son died. Almost two years after seeking asylum in Hong Kong, Immigration Department accepted his claim as substantiated.

Another victim of persecution, a parent of two children, sought the protection of Hong Kong Government in mid-2014 and was recognized a refugee less than a year later with the support of exhaustive documentary proof. Between 3 March 2014, when the Unified Screening Mechanism was launched and 12 February 2015, there were 5 substantiated cases out of 826 claims, maintaining Hong Kong’s effective zero percent acceptance rate (0.61%).

Setting aside vexing doubts about the other 821 claimants denied protection, Vision First is deeply concerned about the harsh and inhospitable treatment of successful claimants. They are in one breath notified a potentially life-changing decision and also informally told they are not welcomed to integrate and reconstruct a new life in Hong Kong.

Despite the promise of not deporting them into harm’s way, claimants are made acutely aware that the prohibition from working stays while they remain confined to the same inadequate welfare provisions they experienced as asylum seekers. Protection (from refoulement) does not come with the right to make a living in Hong Kong.

The Notices of Decisions clearly express the authorities’ position on reluctantly granting temporary asylum until alternative solutions are identified to rid the city of the annoyance of refugees. Claimants are informed that “in the circumstances, you will not be returned to [your country] for the time being”.

Then cases are “passed to the UNHCR for consideration should (you) be recognized as refugees under its mandate and … resettled to a third country as appropriate”. It seems that asylum policies in Hong Kong haven’t evolved from reliance on the United Nations to conveniently sweep away local problems with minimal expense and hassle.

The Notice of Decision warns that, “the making of removal order against you would not be precluded”, i.e. stopped, as “the Immigration Department may consider whether there is any special country other than (your homeland) to which you may return. If any such specific country is identified, you may be removed there.”

Further, the Notices of Decision issued by the Immigration Department states, “if you wish to leave Hong Kong at your own initiative, you may do so notwithstanding your substantiated non-refoulement claims. Please however be reminded that your non-refoulement claims will be treated as withdrawn and will not be re-opened if you leave Hong Kong.”

Finally, another paragraph in the disheartening notices warns, “For the avoidance of doubt, please be also reminded that a person will not be treated as ordinarily resident in Hong Kong … during any period in which he or she remains in Hong Kong only by virtue of a non-refoulement claim, including the period when his or hers non-refoulement claim is substantiated.”

The analysis of such protection documents reveals five warnings from Immigration: 1) we won’t send you back for now; 2) you are not welcome so get the UNHCR to resettle you elsewhere; 3) you are under a removal order and could be deported to another country; 4) you can’t work and won’t receive adequate welfare, so you can volunteer to leave; 5) if you are stuck here for years be aware that you are not treated as ordinarily resident and won’t be allowed citizenship.

As if the above were not depressing enough, the inauspicious Notices conclude with a final warning, “Please also note that your substantiated non-refoulement claim may be reviewed should there be any changes of circumstances and other reasons for considering revocation.”

Hong Kong Immigration’s notices granting international protection to distraught refugees conclude with the word: REVOCATION. It might reflect the spirit in which the Immigration Department reluctantly grants protection following a series of court judgments warning that, “the courts will on judicial review subject the [Immigration] determination to rigorous examination and anxious scrutiny to ensure that the required high standards of fairness have been met.”

Homeless refugees demand proper housing

Feb 18th, 2015 | Housing, Refugee Community, Welfare | Comment

On 17 February 2015, a group of 60 refugees protested at the Social Welfare Department head-office with yet another chorus of complaints to demand greater scrutiny of the current housing crisis that followed the clampdown on refugee slums.

For the third time in a month refugees evicted from illegal huts and shacks made it clear to SWD officials that they are boxed in on four sides:

- They are not allowed to work and are jailed 15 to 22 months upon conviction;

- The 1500$ rent assistance is wholly insufficient in the current housing market;

- Land authorities demand the purging of slums triggering mass evictions;

- Guesthouse rooms are no longer offered as an alternative to homeless refugees.

Pressured by slum lords to leave and unable to secure cheap rooms, 21 refugees represented a hundred colleagues in the slums of Yuen Long and Kam Tin and demanded an urgent and lasting solution to housing needs. They were joined by several homeless refugees from Kowloon and supported by refugee activists and Vision First to lodge formal complaints with SWD social workers.

However, when told that grievances would be referred back to ISS-HK caseworkers, the protesters became agitated. Refugees accused SWD and its contractor of shifting them around, telling refugees in Yuen Long there were rooms in Kam Tin and vice-versa, when inhabitants from both areas sat side-by-side and were familiar with housing prices and shortage.

It was reported that ISS-HK had raised justifications with SWD by accusing the affected refugees of being ‘uncooperative and refusing to accept offers’. But refugees demanded that caseworkers bring such offers to SWD HQ and explain location, occupancy and rental, on top of the legality of certain arrangements. SWD replied that it wasn’t necessary for ISS-HK to bring over the ‘master list’.

It is worth noting that the one refugee who could have died in the blaze that killed Lucky, was lodged by ISS-HK in a guesthouse the next day and not asked to leave. However his colleagues from the same slum, whose huts did not go up in flames, had their rent stopped and faced eviction. Does this point to a government policy to offer guesthouse rooms only to refugees who had a near death experience?

To great consternation and frantic activity in the SWD head-office, the stand-off continued till evening. The press arrived followed by the police. After failing to mediate and suggesting that ISS-HK join the negotiations, the police noted that the protest was peaceful and there was nothing more they could do, so they left. The protesters were preparing to start an occupation and considered options.

Then a senior SWD officer unofficially agreed that the guesthouse solution would not be scrapped, but kept as one option in the protocol in the winding down of slums. An adjustment period is necessary for refugees accustomed to spacious yet dangerous and illegal slum rooms, to transition to multiple-occupancy in apartments. A degree of flexibility and respect is owed to slum-dwellers who were neglected for years in dangerous slums and suddenly evicted.

Further it was accepted that traumatized refugees, and those with medical conditions, should not be threatened with eviction when they fail to secure 1500$ rooms, or refuse to share with strangers, until lasting solutions are identified.

It is hoped that this wave of protest brought home to officials that genuine ‘case by case assessment’ does not equate with stopping rent to force vulnerable refugees overnight into shabby dormitories. This might be unavoidable when rescuing 2000 migrants in one day, but it is unpalatable for veteran refugees such as these protesters who have called Hong Kong home for 5 to 10 years. The guesthouse solution should remain available until suitable flats are secured, least homeless refugees take to the streets again in greater number.

I came to Hong Kong to save my life not work

Feb 17th, 2015 | Housing, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Welfare | Comment

I am a 30 year old South Asian who escaped the breakdown of law and order in a country where corruption protects the powerful who commit crimes with no fear of arrest or prosecution in court. It is meaningless for HK Immigration to claim, “You failed to report the incident to the police [in your country]”, because protection is guaranteed to the highest bidder, not to victims.

One night in 2010 I was smuggled on a speedboat from China to Hong Kong with ten other people. We were very lucky because the next day a powerful typhoon struck and the dangerous crossing could have been deadly. I was very scared at sea on a flimsy fishing boat in pitch darkness. At one point we were hit by a huge wave and we thought we would die.

The smugglers landed us on the coast and told us to walk into the mountains to find the road. They didn’t come with us and we got lost walking at night. For seven days we roamed the mountains in Sai Kung Country Park. We had no food and drank from the streams we crossed. We were relieved when the police arrested us because we were desperately hungry and afraid we wouldn’t make it.

For five years I have been suffering as a refugee. The rent and food we receive is not enough. I have lived three years in the slums, the only place I can rent a room for 1500$. I used to work to pay for a village room, but I suffered a serious injury in the container port. A wave struck the container barge we were offloading and a cargo chain detached and snapped my right arm.

I have heard about two refugees who died under falling containers. I doubt there were any inquiries into their deaths or safety procedures were reviewed. Bosses give refugees dangerous jobs because they know we cannot complain and they won’t have to pay for damages if we get hurt. I did not come to Hong Kong to die, but to live. I risked my life coming here and also working to survive.

Last week my ISS caseworker (name withheld) told me not to protest. He said that a big officer would visit the slums and I should not join the demonstration for safe housing. I stayed in my hut and waited. The big officer did not come. I think ISS tried to block the protest because they don’t want us to talk about our suffering. ISS tell me to find a legal room for 1500$, but they know it is impossible.

I only get some food and 1500$ rent from ISS. In five years they gave me nothing, then last week they gave me a green blanket. I waited five winters for one blanket! Everything I use I collected from nearby garbage dumps where I go on Saturday nights after residents dump old things. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have clothes to wear, a bed to sleep on, a fridge to store food and a stove to cook.

I am not an economic migrant. I came to Hong Kong to save my life, not work or be a beggar.