HKU Magazine – 遠走他方的故事

Apr 15th, 2015 | Advocacy, Immigration, Media, Refugee Community | Comment

遠走他方的故事

Denial of Hong Kong’s refugee past adds to our blinkered policy

Apr 15th, 2015 | Immigration, Media, Rejection | Comment

How many refugees enter illegally from China?

Apr 13th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion | Comment

“Our experience is that walls do not work … Walls can sometimes divert movement, but will not solve the problem”, said the UNHCR chief Mr. Guterres about the doubling of asylum seekers in Europe in 2014.

Hong Kong experienced a surge in the number of people claiming asylum, with 4,634 new cases lodged between March and December last year. Are these new asylum seekers also new arrivals? Have they been absconding for years and only recently came to know of this avenue of protection?

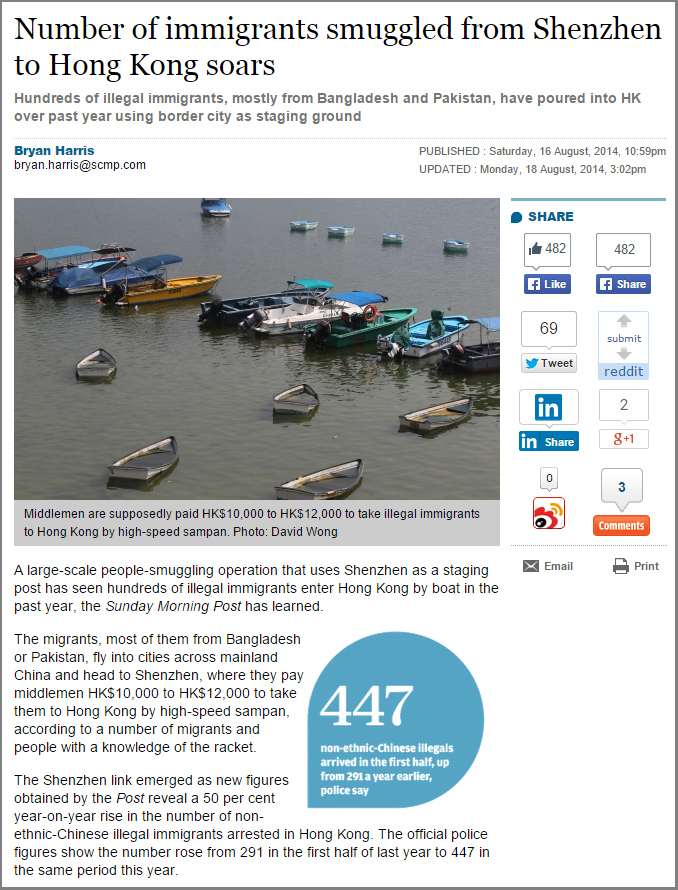

The CIA World Factbook puts Hong Kong’s land border at 30 km and its maritime border at 733 km, most of which is hard to penetrate undetected. We can only guess, but what is hardly a conjecture is that the controlled entrance points at the airport and land crossings are not the only passages into Hong Kong.

At a time when the authorities are targeting undesirable arrivals at the airport, nothing is said about the considerable number of refugees who enter illegally through other ways – some for the second or third time. It appears that the border with China is rather porous and, for the right price, the trip can be arranged with few hassles and no delay. The choices are various: through the fence, over the hills and by speedboats, known colloquially as ‘ferries’.

From many accounts collected by Vision First over the years, entering without a visa is not a matter of difficulty, but unsurprisingly only a question of money. In 2009 the going rate was 4,000 HK$, while today refugees are charged 12,000 to 15,000 HK$ per person.

Why is it so? Who is involved and who profits from this trade? Certainly it does not seem unreasonable, if the government is really worried about a trend that sees ever more requests for protection, to control what is now an extremely porous border. Or is it not a priority?

Here is the narrative of a refugee who recently arrived from Shenzhen that indicates the ease with which arrangements and journeys are made:

“I couldn’t get a visa with my same name so that is why I had to get illegal entry to Hong Kong. We applied for visa for China. It is not easy. I checked online. I checked with tourist agents. We made a tourist package and China sent us the information. We paid 238 USD per person in our group and they issued a letter that we took to the embassy in (our country).”

“Then we bought one-way air tickets to Guangzhou and stayed at a hotel booked online. The second day we took a train to Shenzhen … We didn’t get a stamp on our passport so we didn’t know how long we could stay in China. We waited there.”

“I asked [people] if there is any way to go from there to Hong Kong. A man gave me his mobile number. I used to talk to him every day. He kept telling me, ‘It is not ready. When it is ready I will let you know.’ He asked for 13,500 HKD each person … Every day I called him and asked when we can leave. He said the sea is dangerous, the cops can come there, so you must wait.”

“Almost one month later he suddenly called, ‘Today you must get ready’ … At 6pm we checked out of the hotel. We called a taxi. I called a Chinese guy who told the taxi driver where to go. I don’t know the location where the guy was waiting for us. He saw us and said, ‘You follow me’. I had never seen him before. We walked … then we stopped in a very dark place. He showed us a place on the water.”

“He told us to go sit (on the shore). There were stones in the shallow water and our feet got wet. Later several rowing boats arrived and took us. They rowed for a while and stopped under some trees, along the seashore. We waited longer. Then one of them took a torch and flicked the light a few times. Suddenly a motorboat appeared from the dark …”

“It was an outboard boat made of wood, about 3m long. It had a big engine. I was very scared. In my life it was the first time I had this experience. I was holding on and did not know what would happen. The driver said, ‘Keep still. Don’t move. Head down. Police there.’ He drove very fast …”

“Suddenly I saw my SIM card activated to Smartone, then I knew we were in Hong Kong. I ask him to stop us there as we were afraid and wanted to get off the boat. But he said, ‘No. Just sit there!’ He stopped further up by a small slope. He walked up and asked us to follow him. He called another man who was 20 meters away.”

“I feel that the border between China and Hong Kong is easy to cross. All the time I was praying in China on the bed because even my friends said it is not easy. I was afraid of crossing the sea, but these people made it very easy. Perhaps I was lucky because others say it is very dangerous …”

The other side of the domestic work-refugee nexus

Apr 10th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community, VF Opinion | Comment

There are two sides to the issue of foreign domestic workers falling pregnant and losing their jobs – one is local, the other overseas. On the home front, TVB recently reported on the plight of thousands of maids whose lives were disrupted by pregnancies that are not formulated into policies and, in some cases, are not respected by employers as workers’ rights.

There are some 320,000 foreign domestic helpers (FDH) who account for around 3 per cent of the Hong Kong population. The infamous case of Erwiana symbolised the risks of serious human and labour rights violation by devious employers who might treat maids as disposable slaves. By seemingly failing to enforce the law, the government is not making their plight easier.

Maternity protection is clearly a major concern for hundreds of thousands of female workers in prime child-bearing age. The Employment Ordinance is crystal clear: maids are eligible to 10 weeks’ paid maternity leave (after 40 weeks employment) and the dismissal of a pregnant worker is an offense. An employer who contravenes the provision is liable to prosecution and a fine of HK$ 100,000. But how many employers were successfully prosecuted?

The grim side of this story is that hundreds of pregnant maids seek asylum after being unjustly terminated, or falling out of employment The fear of departing Hong Kong should not be oversimplified. The fear matrix may include complex factors: income loss, illegal work, local partners, prior relationships, support networks, loan sharks, debt bondage, ostracization, religious prohibitions, family shame, customary expectations, racial discrimination and the threat of honour killing.

Contrary to popular belief, any person who overstays in Hong Kong may lodge a protection claim which ought to be approached on the premise that it is genuine until it is proven that it cannot be substantiated. Consequently no adverse inferences may be drawn against ex-maids (pregnant or not) since they might have legitimate claims and several have been recognized as refugees.

Our blog “Understanding the domestic work-refugee nexus” explained that maids are predictably drawn into the asylum sphere for several reasons. A crucial one is that they are not just workers, but are also women who endeavour to foster human relations in a society that diminishes their social worth and dehumanizes their femininity. It is natural that maids and refugees date because both communities are shunned by residents and are often deemed lesser human beings.

The distribution of thousands of boxes of Pampers (and condoms) at Vision First testifies to an escalating problem that the authorities are advised not to underestimate. The big picture is as predictable as it is problematic. Short of sterilization, Immigration has no way of curbing the sexual activity of 320,000 mostly female maids and 10,000 mostly male refugees who find comfort in each other’s arms. Is it surprising that these two communities meet and mingle?

Under the existing scheme, the government offers pregnant maids few choices but to return home under impoverished, unsafe circumstances, or seek asylum. Refugee fathers have little to offer their new families without work rights and adequate welfare assistance. The immigration status of the children follows that of the parents: if neither is a permanent resident, then the children are overstayers under the family’s or a parent’s claim.

The fear matrix becomes crucial. Once the asylum process is concluded, mothers ponder the pros and cons of returning home: Is the fear greater than the prospect of an immiserated existence? Is the danger of returning substantial, or could alternatives be explored given time? Nobody is under any illusion about the zero percent acceptance rate, but the variables are many and timing is key, because it is easier to return with a toddler than an infant. It would be advisable to allow mothers to work again rather than compel them to seek asylum as the only available pathway.

The government is concerned about the escalating cost (640 million HKD according to this report) of the asylum scheme. Priority should thus be given to formulating viable alternatives. Hong Kong society cannot enjoy the privilege of (underpaid) domestic workers without making provisions for natural consequences. We should not turn a blind eye to thousands of women whose rights are violated by policies that fail to envision maternity and its ramifications locally and overseas. Again Hong Kong is attempting to have its cake and eat it.

Foreign Domestic Workers and Pregnancy

Apr 10th, 2015 | Immigration, Legal, Media, Welfare | Comment

Foreign Domestic Workers & Pregnancy Pt. 1 (TVB Pearl)

Foreign Domestic Workers & Pregnancy Pt. 2 (TVB Pearl)

Failing refugees has predictable longterm consequences

Apr 7th, 2015 | Crime, Immigration, Legal, Rejection | Comment

Last week the Liberal Party swung its political machinery into action by petitioning the Security Bureau to tighten visa requirements against South Asian countries to prevent an influx of ‘bogus refugees’. The protest followed the arrival at the end of May of 13 Indians on two non-direct flights, who raised asylum claims with the assistance of the same lawyer, an event reported in the press as suspicious.

Media and official commentary asserted that the arrival of these “13 Indians” was indicative of asylum abuse, rejecting them a priori and without due process, as if refugees fleeing overseas in group was an extraordinary occurrence. Instead was this group stereotyped into suspicious and bogus claimants through the juxtaposition of security, legal and immigration interest that expediently branded them as unwanted and potentially dangerous travelers?

The local media focused on selective information: 1) Immigration is processing over 9000 asylum claims; 2) in 2014 over 4000 new claims were lodged; 3) the top three countries of origin are India, Bangladesh and Pakistan; 4) whereby India accounts for 1760 claimants; 5) visa-free entry from Bangladesh and Pakistan was cancelled three and seven years ago; 6) Indians enjoy visa free entry for periods not exceeding 14 days.

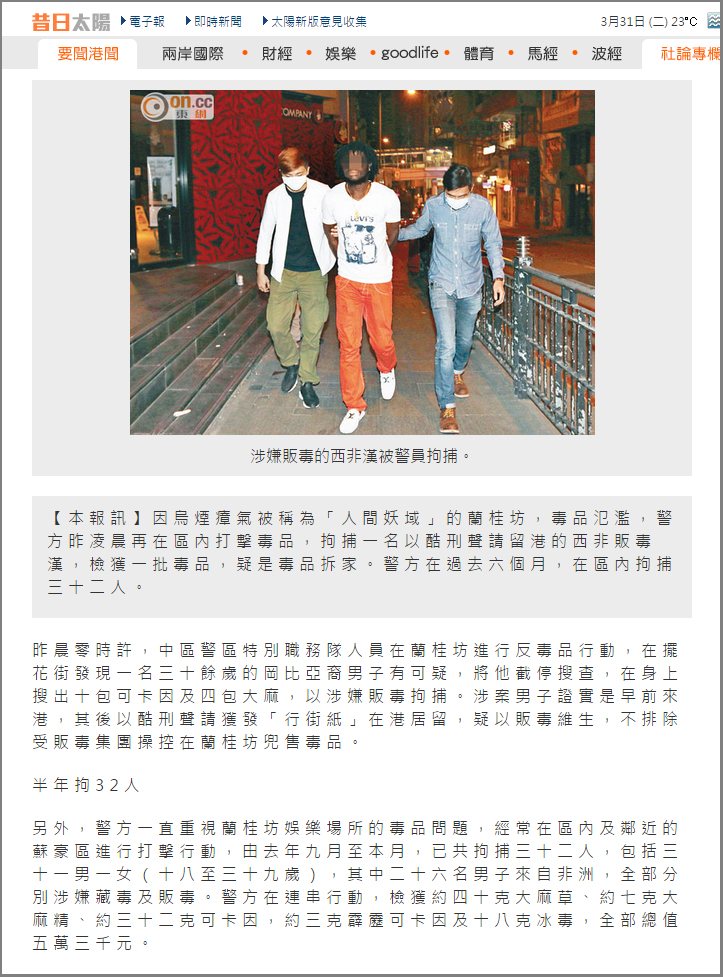

Immigration supported the media coverage ‘admitting that many people abused’ the Unified Screening Mechanism launched in March 2014 following court requirements that cruelty and persecution claims be assessed as well as torture. Immigration produced this data in support of asylum abuse: 1) 166 claimants were arrested in 2014 for working illegally ‘because work is more lucrative than in their countries’; 2) 738 claimants were arrested for theft, assault, drugs and other offenses in 2014; 3) Indian asylum claims rose from 26 a month in 2013 to 75 in 2014; 4) the average asylum claim takes 2.7 years with the longest taking 11 years; 5) asylum claims have risen almost 3 times in the past four years.

An extensive analysis of newspaper article is beyond this blog, though three notable issues deserve being drawn into focus. First, these commentaries say nothing about the unsatisfactiory evolution of asylum policies since 1992 which generated confusion without establishing credible, transparent and expert-driven determinations that truly met high standards of fairness. Over the years, four landmark court rulings caused seismic policy shifts and significant delays which might be worsened by impending “Right to Life” claims under Art. 2 of the Bill of Rights.If past performance is an indication of future results, targeted exploitation of a porous system should not be surprising.

Second, the agency of refugees has been seriously undermined by the administration wrongly, but perhaps intentionally, homogenizing their motivation to escape life-threatening situations with that of irregular migrants primarily motivated by voluntary economic imperatives. In the public discourse an overlap exists between the legal status of asylum seekers, treated primarily as overstayers, and illegal immigrants, a confusion that blurs the boundaries normally defining these two categories.

Third, reflective consideration should be given to the laws, administrative policies and social norms that construct the exclusion spaces in which refugees are compelled to make a living without work rights or adequate welfare assistance. Within this optic, it is neither arduous nor commendable for law enforcement to intercept refugees in construction sites, illegal workshops, underground factories and recycling yards where they scrape an unenviable existence. Should 10,000 claimants abide strictly to laws and policies by panhandling on Hong Kong streets?

This highlights the need for an analysis of the reason why refugees expect to earn a living, in part as a way to regain a sense of self-respect lost during flight. Refugees hope to assume a productive role in society and thereby to improve their wellbeing and social and economic status. As one African refugee remarked, “In Hong Kong I have safety, but I don’t have a good life, because a good life is when you work on your own.”

Are refugees a genuine treat to Hong Kong’s security, stability and prosperity, or does the administration need to reconsider and reformulate a questionable asylum process?

The treatment of refugees by SWD can lead to criminal acts

Mar 31st, 2015 | Crime, Food, Housing, Immigration, Legal, Welfare | Comment

Written by Christopher McNulty

It needs to be considered that the way in which Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department (SWD) treats refugees can lead to refugees committing criminal acts. This will be explained by defining and discussing the criminological theories of opportunity and labelling and explaining how current SWD policies might lead refugees to commit criminal acts.

Opportunity theory can be defined as, “offenders having inadequate or inappropriate means or opportunities to achieve certain goals relative to other people in society” (White, 2014, p. 71). Considering refugees in Hong Kong using this theory, it can be argued that crime is generated by this type of treatment. For example, if refugees don’t have adequate means of living and opportunities to better themselves through education and work, there is a chance they will try to better themselves through ‘illegal’ activities such as work performed without authorization. As reported in the South China Morning Post, “asylum seekers awaiting the outcome of their claim with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), recognised refugees awaiting resettlement to another country and torture claimants are banned from doing paid or unpaid work” (Chan, 2013).

Looking at this through opportunity theory, it can take years for refugees to be screened and possibly resettle in another country and, while waiting, they cannot work to better themselves and earn money for their family. Using this example there is a likelihood that if a refugee family needed money for rent, food, clothes or the children’s school and if the only way to achieve this was stealing or working illegally, they would have no choice but to commit criminal acts to meet what most people would agree are basic daily needs, in this case, unmet by the SWD.

Labelling theory can be described as society labelling an individual, which in turn can cause the individual becoming influenced by the label and acting out that labelled behaviour (Holmes, 2012, p. 250). It can be argued that refugees can be stigmatised due to the current system and laws in place. For example, refugees can be seen by the Hong Kong public as being dependant on the SWD and not searching for jobs, as they are not aware of the current government policies which prohibit them from working. This type of stigmatization can cause refugees to be always seen by the public as individuals who are content being dependant on welfare and not wanting to work. This can lead to refugees believing social change will never occur and becoming influenced by the label and turn to conducting criminal acts such as theft and working illegally.

In conclusion, as shown through the criminological perspectives of opportunity and labelling, the current policies of the HK SWD can cause refugees to commit criminal acts due to them not enjoying adequate support and being labelled by the general public as continuously dependant on welfare and not looking for employment. To create a stronger relationship between refugees and the government, refugee policy needs to change to minimise the potential of criminal acts being committed by refugees trying to meet rent payments, purchase essential foodstuffs and making ends meet.

Currently in the media: