A lost tribe in the city: health status and needs of African asylum seekers and refugees in Hong Kong

Oct 4th, 2016 | Media, Medical, Refugee Community | Comment

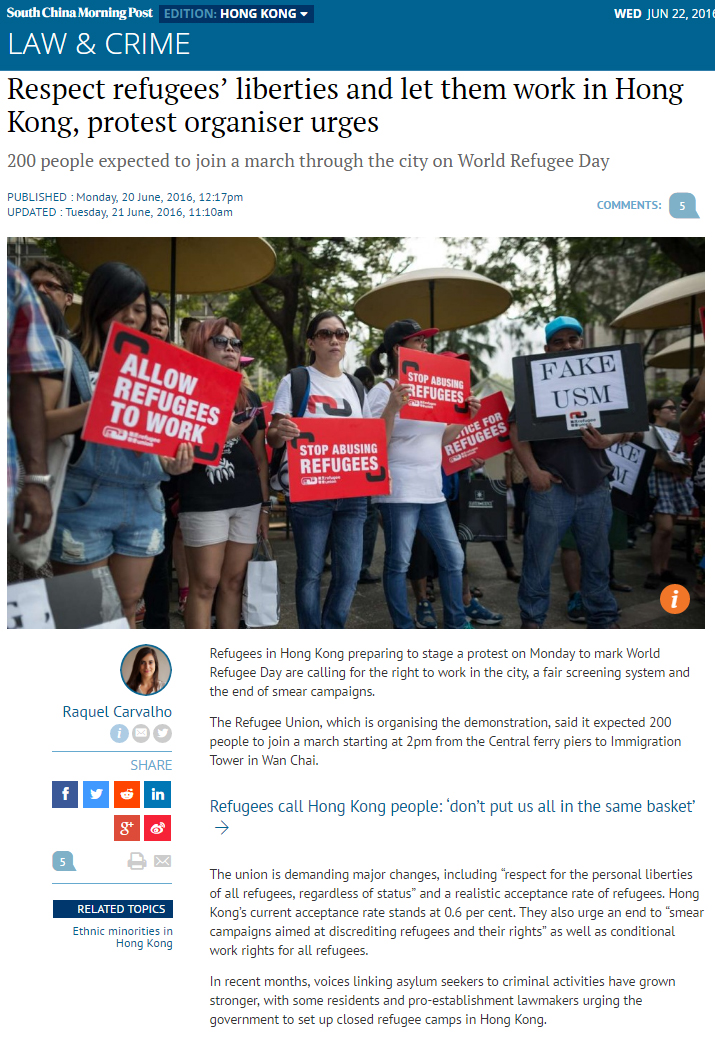

Respect refugees’ liberties and let them work in Hong Kong, protest organiser urges

Jun 20th, 2016 | Immigration, Medical, Rejection | Comment

A local case of cruel, inhuman treatment and punishment?

Sep 10th, 2015 | Immigration, Medical, Rejection, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

In recent months the government has waged a war of words against asylum “abuse” in general and claimants arriving from India in particular.

Hong Kong might not be a city “of extraordinary compassion”, as Prime Minister David Cameron said about Britain, but crucially the High Court requires that, “a refugee claimant deserve sympathy and should not be left in a destitute state during the determination of his status. However, his basic needs such as accommodation, food, clothing and medical care are provided by the Government.”

Further, the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance unequivocally prescribes that, “No one shall be subjected to torture or the cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” (Art. 3).

Despite such exquisite guarantees of refugee rights and government duty, in the evening of 22 August 2015, a destitute, starving, homeless and sick refugee collapsed in the streets of Jordan and was rushed unconscious by ambulance to Queen Elizabeth Hospital where he was treated for 18 days. The diagnosis was loss of consciousness, sepsis, psoriasis and alcohol dependence.

“I lost consciousness and hit my head,” recalls Singh, “Someone called an ambulance and I woke up in the hospital. I drank beer for the pain and itchiness of these sores covering all my body. It started small but got very worse [in the] six months [that] I waited for Immigration to give me new immigration paper. I had no help, no food and could not go to the clinic. For long time I sleep in the streets.”

In 2010 the Marine Police arrested Singh as he entered illegally from China. He was released from Immigration detention after lodging a torture claim based on his fear of death threats which has not yet been determined under the Unified Screening Mechanism (USM). Around May 2012 he lost his Recognizance Form 8 and stopped reporting to Immigration for fear of being deported.

A refugee friend recalls the night in March when he encountered him, “It was freezing cold. I saw a man shivering on a bench in the park. I asked where he was from and what happened. He told me he was from India. He was sick and very desperate. I offered him food and the next day I took him to the Refugee Union. Two days later I took him to Immigration to apply for a new paper.”

According to Singh and his friend, who speaks fluent English and assisted him throughout, Immigration was fully informed about Singh’ predicament and especially about his medical condition that an officer agreed “was very critical”. And yet Mr. Singh was told to wait “one or two weeks”, repeatedly, until he grew the suspicion that Immigration planned to arrest and deport him.

Ignorance of his rights exacerbated the suffering Singh endured until he lost consciousness. The asylum process however showed little sympathy and did not prevent destitution by providing essential shelter, food and, most critically, medical treatment. On one occasion Singh says, “My officer told me that if I want to go back to India they will arrange the ticket immediately.” Yet his request for a replacement Recognizance Form has been ignored since March 2015.

Queen Elizabeth Hospital compounded Singh’s ordeal by demanding $25,870 upon discharge and withholding essential medications until the bill was settled. The penniless and despairing refugee had no option but to walk out of the hospital in shame. “They told me to go to the clinic in Jordan for treatment, but first I must pay the hospital bill. How can I pay? I have no money,” he laments.

Paranoid by fears of abuse and anxious to reduce the number of asylum seekers, Hong Kong Government is waging a war of attrition against refugees with forced hardship deployed as the main weapon. This approach is deeply regrettable as the effect on asylum abusers is questionable, while the impact on the weakest refugees is obvious. The time has come for the authorities to look in a mirror and figure out why the asylum process is failing everyone – vulnerable refugees especially.

UPDATE – The day following this blog, Singh was issued with a new Recognizance Form and collected medication from Queen Elizabeth Hospital that waved all charges.

True protection eludes a recognized refugee

Apr 29th, 2015 | Immigration, Medical, Personal Experiences, Rejection, VF Report | Comment

After five years of deep emotional and economic suffering in Hong Kong, on 15 January 2015 Ali was rushed to the hospital with pain in his chest. He recalls, “The medical officer informed me that one of my heart vessels is blocked. They (need to perform an) angioplasty to fix a stent in the blocked vain. But I have to pay 20,000 HK$ myself as the stent is not available from the hospital (free for refugees). I told him that due to my status, it is not possible for me to pay such a huge amount … ISS case worker and UNHCR said sorry that we do not have funds for that purpose.”

Who is Ali? Ali is a 62 year-old recognized refugee from Pakistan in Hong Kong since January 2010. He spent several winters freezing in a container abandoned in a Kam Tin recycling yard. In the summer his home became unbearably hot. Before rental deposits were introduced for refugees, Ali accepted such limited hospitality from residents offering temporary shelter. By living in a possible illegal work place, the Pakistani defied the common assumption that his countrymen abused asylum to work in Hong Kong.

For five years, Vision First followed closely Ali’s asylum experiences in our inhospitable city.

Ali feels betrayed by Hong Kong’s promises of protection, “In January 2010 I left my country, business, mother, wife, children, brothers, sisters, friends and relatives hoping that Hong Kong Government and UNHCR will appreciate our sacrifices in the war against terrorism by opening their hearts and help us in standing again on our feet. But all our expectations were ruined by the different functionaries of the government and UNHCR.”

In May 2011 the Immigration Department rejected Ali’s torture claim at appeal. He was stoically terse, “It is a childish decision!” The rejection by UNHCR in December 2012 was traumatizing, as it crushed his trust in the international agency. When Legal Aid rejected his application to judicially review his CAT rejection, the disheartened family man hit rock bottom. Sick and depressed, Ali seemed on the verge of giving up more than his bid for asylum. In those dark days, only family thoughts kept him going, “I have many burdens with my family. How can I help them? The whole family is looking to me. They are stuck. They want to know when they can come and join me.”

Conspiracists might be forgiven for speculating about the baffling backpedaling by UNHCR which unexpectedly confirmed his status as a refugee on 29 April 2014. It might not be a coincidence that Ali’s lawyers had reversed the Legal Aid decision and prepared a well-document, arguable case that might have forced Immigration to reconsider its decision. Ali suspects that the government put pressure on UNHCR to resolve his claim and stop legal proceedings.

At the time he was hospitalized, Ali was informed that since his condition had not reached a ‘life threatening state’, the hospital could not proceed with free surgery and he would have to pay for the stent himself. Five years in limbo without the right to work dilapidated Ali personal resources. Today he is truly destitute. ISS-HK referred him to SWD which unempathically stated that they would not pay until his condition deteriorated.

Let’s face it. Ali has been treated poorly from the day he arrived and was reduced to living in a shipping container for years. His family was displaced and fell from relative prosperity to grim poverty. Now Ali spends the days bedridden in a room that appears to be an illegal structure. He is afraid his heart will fail overnight. He hardly dares to walk outside for fear of collapsing in the street, which ironically might be the only chance he has to receive the necessary surgery.

Hospitals, ISS-HK and SWD kick away responsibility like a ball. Is it reasonable to ask a sick refugee to raise money himself to save his life despite being granted international protection? What meaning does the status of refugee carry for UNHCR, ISS-HK, SWD and the government? Who will be held accountable in a worst case scenario for such absurd conditions of institutional punitive confinement? Hong Kong should step up and honor Ali’s protection with the peace of mind and wellbeing it ought to entail.