Pro bono legal team enters CIC to secure release of refugees

May 8th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Rejection | Comment

May 6th of 2015 is likely to be a day many refugees detained by the Director of Immigration at the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) will not easily forget. The Refugee Union had taken instructions from over 30 detainees to arrange a legal visit by a pro bono legal team to advise them on their asylum claims, the legality of the asylum claim procedures, conditions and legality of detention and to secure their release. Since a group visit by a pro bono legal team had not occurred for some time, the refugees were hopeful whilst not knowing what to expect.

The legal team comprised Barristers Mr. Mark Sutherland and Mr. Robert Tibbo, both non-executive directors of Vision First, who scheduled valuable time to provide free legal advice to the detainees, some of whom have indeed been unlawfully detained. Counsel were instructed by solicitors Mr. Tam Kam Tong and Mr. Chris Lucas respectively, who were supported by interpreters – everyone acting on a pro bono basis.

The Director of Immigration had been notified of the legal visit to a number of refugees for the purposes of assessing “current detention at CIC and to advise on possible claims under Article 2 of the Bill of Rights Ordinance.” The legal visit was also to focus on the procedure for judicial review. Led by Superintendent W.S. Kwong, Immigration officers and staff were helpful throughout the particularly busy day.

Sutherland remarked, “There are several refugees who have been locked up since they arrived despite having lodged claims for asylum. In some cases, their interviews haven’t even started. This is clearly a prima facie case of unlawful detention and immediate release has been requested.” Tibbo added, “One youth from South Asian was so traumatized by his treatment by the Director of Immigration at CIC that he gave up and withdraw his non-refoulement protection claim. They are being warehoused in a similar way to Australian off-shore detention camps.”

A sense of encouragement grew among refugees from morning till afternoon. The initial uncertainty about the magnitude of events lifted as the first clients returned to the common rooms to share their experiences. Tibbo observed, “It was like a fire was spreading inside CIC. The refugees knew their lawyers were there and they might be released soon. Clients were coming in to the meeting rooms and everyone was fired up and happy – there was a resurgence of hope that could been seen in their eyes and faces.”

After lunch, while inside CIC, Sutherland came across quite per chance two visitors who turned out to be the Justices of the Peace (JPs) assigned to inspect CIC. JPs are the only independent professionals granted unrestricted access to the centre, where they may speak to detainees without appointment and request copies of detention files. The two gentlemen were clearly alarmed by the grave concerns expressed by Counsel which had arisen out of the legal visit. The JPs kindly held two meetings with the legal team on the same day. They requested a full report of the findings. Interestingly, Vision First was in the process of preparing to make contact with the JP’s Office to seek assistance in relation to detention concerns. Sutherland has since conveyed the matter in writing to the JPs in question.

By 5 p.m., the legal team requested the Director of Immigration to immediately release 6 (six) refugees who have been arbitrarily and unlawfully detained by the Director of Immigration. Their release is expected imminently. It is noteworthy that several refugees on the original list had already been released from detention prior to the legal visit.

It is believed that the legal team’s effort will have an impact on the way certain matters are carried out behind the secretive walls of Immigration detention. It now appears clear that refugees are being unlawfully detained in CIC whist they have outstanding non-refoulement claims.

In reality more than occasional pro bono efforts are needed to ensure high standards of fairness in Immigration detention and to hold the Director of Immigration, Mr. K.K. Chan to account. There should be a panel of lawyers assigned either by The Director of Legal Aid and/or The Duty Lawyer Service to meet this crucial need. These lawyers should be on hand at CIC to offer on the spot legal advice to detainees, regarding their detention and with the authority to launch habeas corpus proceedings, if necessary.

The present lacuna in the provision of free legal advice regarding detention plays into the hands of the Director of Immigration and militates towards longer periods of unchecked, unlawful detention.

Why is Hong Kong hostile to refugees?

May 6th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Rejection, VF Opinion | Comment

It was hard to answer the question of a visitor to Vision First who sought to understand the caustic environment navigated by refugees with a slim chance of securing protection in an indifferent city. Ironically, Hong Kong has long had a history of welcoming refugees (1.5 million between the 1930s and 1970s), but its sympathy and support of persecuted foreigners dwindled regrettably as residents became richer.

The government mantra is well rehearsed, “Non-refoulement claims lodged under the USM are not asylum claims. The Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol have never applied to Hong Kong. The Government maintains a firm policy of not granting asylum to or determining the refugee status of anyone. Our policy objective is to screen … and to remove rejected claimants from Hong Kong as soon as possible. Lodging a claim does not change the fact that non-refoulement claimants are illegal immigrants or overstayers.”

The results of such a policy appear skewed towards removal. Between 2009 and 2014, Immigration screened 5581 claims and substantiated just 25. It is noteworthy that in 6 years Immigration failed to grant protection to a single asylum seeker among 2166 Pakistani, 1760 Indians and 1237 Bangladeshi. Hong Kong has never protected a claimant from these countries. By contrast, in 2013 Australian protection grants produced very different results: Pakistani 80.4%, Indians 6.3% and Bangladeshi 42.7% at first instance (p. 20). Astonishing it is that Pakistani scored 94.9% including appeals (p. 30). How does it compare to Hong Kong’s achievements?

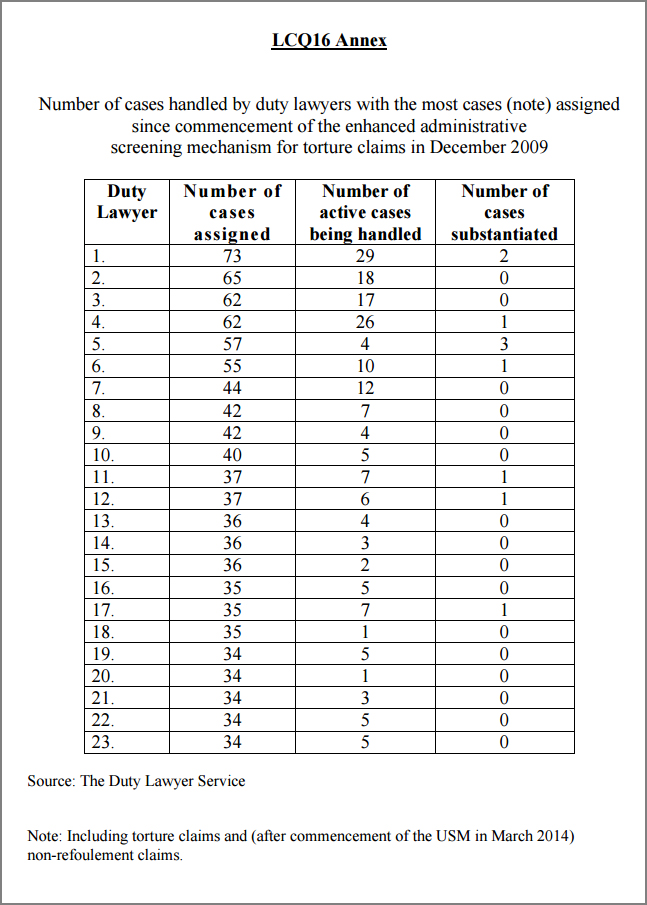

Despite profuse assurances to the contrary, it appears that Hong Kong Government has abdicated its obligation to protect refugees and has instead prioritized rejection and removal. An elaborate performance by 480 lawyers ‘who have received specialised training’ has done little to improve the effective zero percent acceptance rate. To the contrary, the authorities are focused on cost-cutting to reduce the $644 million spent on claimants, including legal aid up 86% last year.

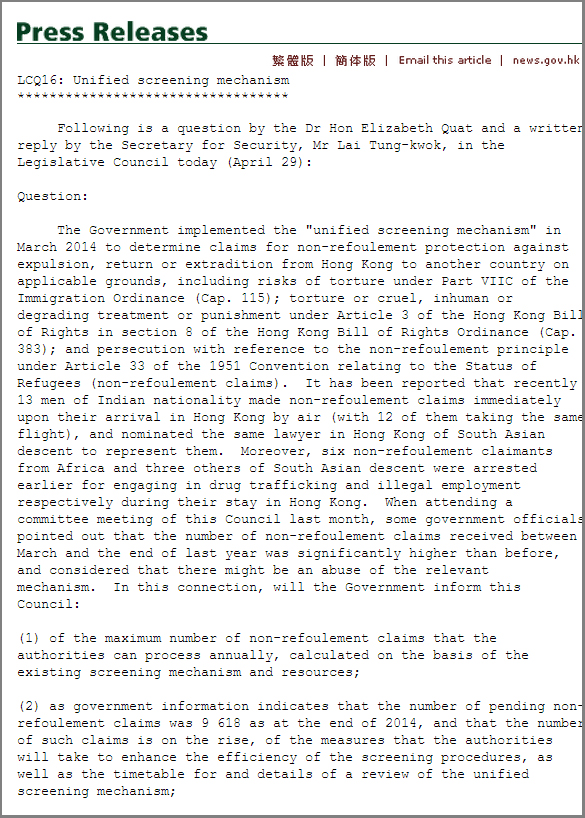

Stringent immigration control and deterrent welfare were ingeniously deployed to deter asylum seekers from remaining in Hong Kong, but their number doubled in 2014 to 9618, reflecting worrying global trends. Immigration is presumably feeling the pressure and this year plans to determine 2000 claims, which might fail to reduce the total ‘with new claims coming in at more than 300 per month since early 2014.’

In an obfuscated environment of rejection and expediency, is it possible that some refugees might be removed or deported to their country of origin at a risk of life and limb? It is hard to make factual assessments, as the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) remains off-limits to rights advocates and detainees may only be visited by appointed lawyers. Refugees denied release on recognizance are unlikely to enjoy adequate legal advice, or second opinions on their claims.

In this potential black hole, can Immigration be trusted to adhere scrupulously to high standards of fairness, respect fundamental refugee rights and assess claims in a non-adversarial manner as required by law? Acting on a pro bono basis, barristers Robert Tibbo and Mark Sutherland, non-executive directors of Vision First, visited CIC on 6 May 2015 to take instructions from 24 detainees who sought the assistance of the Refugee Union against imminent removal orders. It was reported that 5 had already ‘left from Hong Kong International airport’ with no further details.

Security Bureau update on the Unified Screening Mechanism

Apr 30th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Government, Immigration, Legal | Comment

Hong Kong requires a legal board in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre

Apr 30th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community | Comment

A year before the Unified Screening Mechanism was launched in March 2014, Vision First campaigned vigorously against Immigration Department’s apparently biased conduct and ostensible refusal to entertain CIDTP claims during the torture claim screening process. It is alarming that presently the problem is being repeated in relation to “Right to Life Claims.”

The rule of law in Hong Kong requires that every asylum claim be assessed with “anxious scrutiny and high standards of fairness” before Immigration exercises its statutory power of removal or deportation (CFA Prabakar case, Jun 2004) . This gives rise to an obligation to recognize the right not to be subject to torture, CIDTP and persecution for persons having no right to enter Hong Kong, including refugees detained in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) – some who have never been released on recognizance.

Backed by reports from claimants detained for prolonged periods, Vision First is concerned by the secretive nature of detention at CIC. The availability of publicly funded lawyers and interpreters at interviews in CIC is not a guarantee of high standards of fairness when refugees are denied second opinions and there is no legal board to offer advice to those in need.

A Middle Eastern refugee was detained over 8 months and resisted several attempts at removal. He reports, “Immigration refused to believe me. They forced me to the airport but I resisted. I knew my rights and demanded to be released to prove my case. Others who didn’t speak English were not as lucky as me.”

A refugee from India had his case rejected as he languished for 10 months in CIC. He recalls, “My lawyer told me to drop my claim and leave Hong Kong. He refused to help me with the appeal. I thought he was serving the interests of Immigration.”

In April 2015, Vision First met with the Hong Kong Bar Association to raise concerns about the respect of fundamental refugee rights in CIC detention. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Immigration is arbitrarily denying applications for “Right to Life” protection in the centre. There is a widely held belief that the zero percent acceptance rate reflects a strategy to deny protection despite the potential risk of life and limb for those expelled from Hong Kong.

Detainees would be alarmed to know that between 2009 and 2014 Immigration rejected 99.54% of 5581 claims determined. It is doubtful that any one of the 25 substantiated claimants was recognized inside CIC and released with protected status. Immigration should report how many claimants from which countries are detained at the airport, screened in detention and removed without being released on recognizance. What assurances can be made that they were treated fairly?

Hong Kong urgently requires a legal board to independently advise claimants in Immigration detention and prisons, monitor the implementation of asylum practices and ensure that the Unified Screening Mechanism pays more than lip service to high standards of fairness. Until that day comes it is suspected that the screening system lacks credibility, not refugees.

A month has passed since Vision First wrote an open letter to Immigration raising a series of questions in connection with Right to Life claims. Disappointingly no substantive reply was received from the Director of Immigration. In early April the Refugee Union established a 24-hour helpline for CIC detainees who can only make two local phone calls a month. The union has been contacted by dozens of refugees who appealed for independent legal assistance with asylum claims and lamented the treatment they received away from the public eye.

Welfare punishment is a doubtful deterrent

Apr 27th, 2015 | Crime, Housing, Legal, VF Report, Welfare | Comment

The Hong Kong government has a preference to describe asylum in negative terms: “Non-refoulement claimants in Hong Kong are illegal immigrants or overstayers, even if their claim is substantiated … they may not take up employment in Hong Kong; violation of the relevant provisions is a criminal offence punishable on conviction to a fine of up to level 5 ($50,000) or to imprisonment for three years … the sentencing guideline in respect of the relevant provision states that 15 months’ imprisonment should be imposed on a person convicted of an offence.” (Finance Committee 2015-16)

Very few lawyers stand apart for attaching the utmost importance to refugee rights and striving to ensure such rights are respected and safeguarded in the interest of the asylum community and the city’s reputation. The reality is that in most cases they have to represent clients pro bono.

In February 2014, barrister Robert Tibbo obtained leave to make an application for the judicial review of the torture claim of a South Asian woman whose appeal was dismissed without an oral hearing. Her council, a non-executive director of Vision First, argued that various factual matters relevant to the case had not been addressed by the adjudicator who cherry-picked country of origin information.

The woman sought refuge in Hong Kong in 2005 to escape from threats to her life and safety due to her political activities and the serious abuse she received from her husband affiliated to an opposing political party. As if her struggle for protection was not enough, a decade later she stood before the bench in Eastern Magistracy to answer to charges of working illegally.

In 2013, the woman was arrested by police at the back of a restaurant where she occasionally washed dishes for exploitative wages. For months she had paid cash for a dilapidated subdivided room, because the landlord refused to accept bank transfers from ISS-HK and she was unable to find alternative accommodation within the paltry rental budget that was then 1200 HK$.

It is not uncommon for refugees to rent the cheapest rooms from landlords who prefer cash payments to reporting bank transaction in income statements. In such cases tenants are obliged to secure cash somehow, or risk being homeless. Under the circumstances, the great majority of refugees seek employment in the informal economy and risk arrest, prosecution and jail for attempting to make ends meet.

Interestingly this woman’s situation ticks several failures in the current asylum policy: 1) denial of protection; 2) prolonged determination of claims; 3) prohibition from working, and 4) insufficient welfare assistance, which in this case included failure by ISS-HK to secure suitable accommodation for a vulnerable woman. Robert Tibbo is seeking a stay of prosecution arguing that systemic failures placed his client in a predicament in which she worked to avoid sleeping in the street.

At a hearing in April 2015, the magistrate suggested that a judicial review be sought against the Director of Immigration who sets the recognizance conditions, including the prohibition from taking up employment. The argument is that if the government openly met the basic needs of refugees and signed tenancy agreements, then refugees would not be compelled to work illegally.

Robert Tibbo explains, “This case is likely to go to the Court of Final Appeal. It is hardly unique since countless refugees struggle daily to pay necessary costs not met by ISS-HK. My client is a victim of an intentional failure by the Government to meet the basic needs of refugees who, when facing similar charges, often plead guilty to avoid stiffer sentences while cognizance that they were entrapped. This case has the potential of changing the system.”

The other side of the domestic work-refugee nexus

Apr 10th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community, VF Opinion | Comment

There are two sides to the issue of foreign domestic workers falling pregnant and losing their jobs – one is local, the other overseas. On the home front, TVB recently reported on the plight of thousands of maids whose lives were disrupted by pregnancies that are not formulated into policies and, in some cases, are not respected by employers as workers’ rights.

There are some 320,000 foreign domestic helpers (FDH) who account for around 3 per cent of the Hong Kong population. The infamous case of Erwiana symbolised the risks of serious human and labour rights violation by devious employers who might treat maids as disposable slaves. By seemingly failing to enforce the law, the government is not making their plight easier.

Maternity protection is clearly a major concern for hundreds of thousands of female workers in prime child-bearing age. The Employment Ordinance is crystal clear: maids are eligible to 10 weeks’ paid maternity leave (after 40 weeks employment) and the dismissal of a pregnant worker is an offense. An employer who contravenes the provision is liable to prosecution and a fine of HK$ 100,000. But how many employers were successfully prosecuted?

The grim side of this story is that hundreds of pregnant maids seek asylum after being unjustly terminated, or falling out of employment The fear of departing Hong Kong should not be oversimplified. The fear matrix may include complex factors: income loss, illegal work, local partners, prior relationships, support networks, loan sharks, debt bondage, ostracization, religious prohibitions, family shame, customary expectations, racial discrimination and the threat of honour killing.

Contrary to popular belief, any person who overstays in Hong Kong may lodge a protection claim which ought to be approached on the premise that it is genuine until it is proven that it cannot be substantiated. Consequently no adverse inferences may be drawn against ex-maids (pregnant or not) since they might have legitimate claims and several have been recognized as refugees.

Our blog “Understanding the domestic work-refugee nexus” explained that maids are predictably drawn into the asylum sphere for several reasons. A crucial one is that they are not just workers, but are also women who endeavour to foster human relations in a society that diminishes their social worth and dehumanizes their femininity. It is natural that maids and refugees date because both communities are shunned by residents and are often deemed lesser human beings.

The distribution of thousands of boxes of Pampers (and condoms) at Vision First testifies to an escalating problem that the authorities are advised not to underestimate. The big picture is as predictable as it is problematic. Short of sterilization, Immigration has no way of curbing the sexual activity of 320,000 mostly female maids and 10,000 mostly male refugees who find comfort in each other’s arms. Is it surprising that these two communities meet and mingle?

Under the existing scheme, the government offers pregnant maids few choices but to return home under impoverished, unsafe circumstances, or seek asylum. Refugee fathers have little to offer their new families without work rights and adequate welfare assistance. The immigration status of the children follows that of the parents: if neither is a permanent resident, then the children are overstayers under the family’s or a parent’s claim.

The fear matrix becomes crucial. Once the asylum process is concluded, mothers ponder the pros and cons of returning home: Is the fear greater than the prospect of an immiserated existence? Is the danger of returning substantial, or could alternatives be explored given time? Nobody is under any illusion about the zero percent acceptance rate, but the variables are many and timing is key, because it is easier to return with a toddler than an infant. It would be advisable to allow mothers to work again rather than compel them to seek asylum as the only available pathway.

The government is concerned about the escalating cost (640 million HKD according to this report) of the asylum scheme. Priority should thus be given to formulating viable alternatives. Hong Kong society cannot enjoy the privilege of (underpaid) domestic workers without making provisions for natural consequences. We should not turn a blind eye to thousands of women whose rights are violated by policies that fail to envision maternity and its ramifications locally and overseas. Again Hong Kong is attempting to have its cake and eat it.

Foreign Domestic Workers and Pregnancy

Apr 10th, 2015 | Immigration, Legal, Media, Welfare | Comment

Foreign Domestic Workers & Pregnancy Pt. 1 (TVB Pearl)

Foreign Domestic Workers & Pregnancy Pt. 2 (TVB Pearl)

Failing refugees has predictable longterm consequences

Apr 7th, 2015 | Crime, Immigration, Legal, Rejection | Comment

Last week the Liberal Party swung its political machinery into action by petitioning the Security Bureau to tighten visa requirements against South Asian countries to prevent an influx of ‘bogus refugees’. The protest followed the arrival at the end of May of 13 Indians on two non-direct flights, who raised asylum claims with the assistance of the same lawyer, an event reported in the press as suspicious.

Media and official commentary asserted that the arrival of these “13 Indians” was indicative of asylum abuse, rejecting them a priori and without due process, as if refugees fleeing overseas in group was an extraordinary occurrence. Instead was this group stereotyped into suspicious and bogus claimants through the juxtaposition of security, legal and immigration interest that expediently branded them as unwanted and potentially dangerous travelers?

The local media focused on selective information: 1) Immigration is processing over 9000 asylum claims; 2) in 2014 over 4000 new claims were lodged; 3) the top three countries of origin are India, Bangladesh and Pakistan; 4) whereby India accounts for 1760 claimants; 5) visa-free entry from Bangladesh and Pakistan was cancelled three and seven years ago; 6) Indians enjoy visa free entry for periods not exceeding 14 days.

Immigration supported the media coverage ‘admitting that many people abused’ the Unified Screening Mechanism launched in March 2014 following court requirements that cruelty and persecution claims be assessed as well as torture. Immigration produced this data in support of asylum abuse: 1) 166 claimants were arrested in 2014 for working illegally ‘because work is more lucrative than in their countries’; 2) 738 claimants were arrested for theft, assault, drugs and other offenses in 2014; 3) Indian asylum claims rose from 26 a month in 2013 to 75 in 2014; 4) the average asylum claim takes 2.7 years with the longest taking 11 years; 5) asylum claims have risen almost 3 times in the past four years.

An extensive analysis of newspaper article is beyond this blog, though three notable issues deserve being drawn into focus. First, these commentaries say nothing about the unsatisfactiory evolution of asylum policies since 1992 which generated confusion without establishing credible, transparent and expert-driven determinations that truly met high standards of fairness. Over the years, four landmark court rulings caused seismic policy shifts and significant delays which might be worsened by impending “Right to Life” claims under Art. 2 of the Bill of Rights.If past performance is an indication of future results, targeted exploitation of a porous system should not be surprising.

Second, the agency of refugees has been seriously undermined by the administration wrongly, but perhaps intentionally, homogenizing their motivation to escape life-threatening situations with that of irregular migrants primarily motivated by voluntary economic imperatives. In the public discourse an overlap exists between the legal status of asylum seekers, treated primarily as overstayers, and illegal immigrants, a confusion that blurs the boundaries normally defining these two categories.

Third, reflective consideration should be given to the laws, administrative policies and social norms that construct the exclusion spaces in which refugees are compelled to make a living without work rights or adequate welfare assistance. Within this optic, it is neither arduous nor commendable for law enforcement to intercept refugees in construction sites, illegal workshops, underground factories and recycling yards where they scrape an unenviable existence. Should 10,000 claimants abide strictly to laws and policies by panhandling on Hong Kong streets?

This highlights the need for an analysis of the reason why refugees expect to earn a living, in part as a way to regain a sense of self-respect lost during flight. Refugees hope to assume a productive role in society and thereby to improve their wellbeing and social and economic status. As one African refugee remarked, “In Hong Kong I have safety, but I don’t have a good life, because a good life is when you work on your own.”

Are refugees a genuine treat to Hong Kong’s security, stability and prosperity, or does the administration need to reconsider and reformulate a questionable asylum process?

Complaint to the Legislative Council Redress System

Apr 1st, 2015 | Advocacy, Food, Housing, Legal, VF updates, programs, events, Welfare | Comment

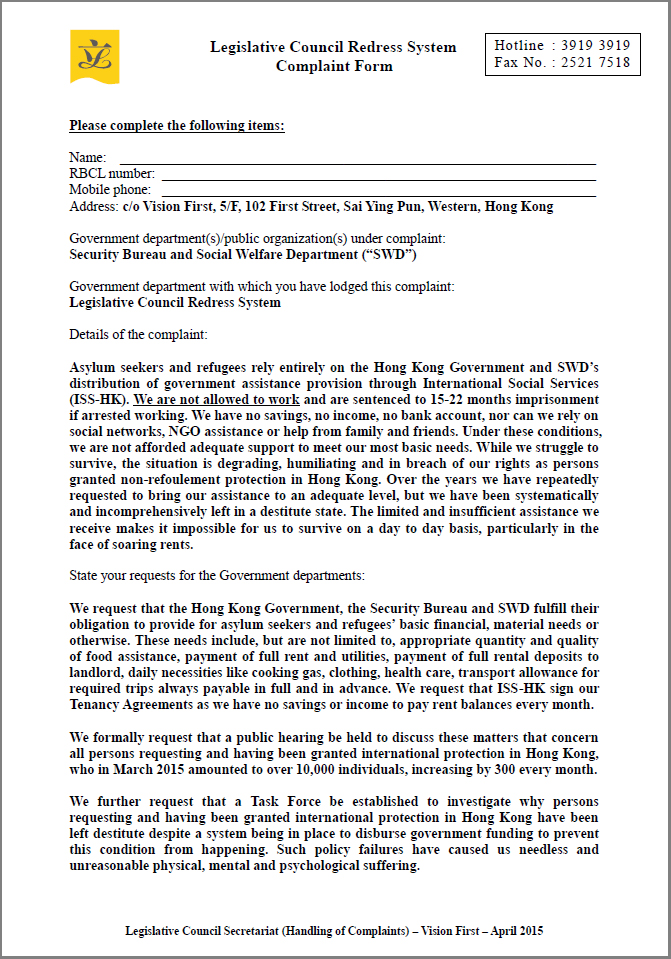

Asylum seekers and refugees rely entirely on the Hong Kong Government and Social Welfare Department (“SWD”) distribution of government assistance provision through International Social Services (ISS-HK). They are not allowed to work and are sentenced to 15-22 months imprisonment if arrested working. They have no savings, no income, no bank account, nor can they rely on social networks, NGO assistance or help from family and friends. Under these conditions, they are not afforded adequate support to meet their most basic needs. While they struggle to survive, the situation is degrading, humiliating and in breach of their rights as persons granted non-refoulement protection in Hong Kong. Over the years they have repeatedly requested to bring their assistance to an adequate level, but they have been systematically and incomprehensively left in a destitute state. The limited and insufficient assistance they receive makes it impossible for them to survive on a day to day basis, particularly in the face of soaring rents.

Vision First request that the Hong Kong Government, the Security Bureau and SWD fulfill their obligation to provide for asylum seekers and refugees’ basic financial, material needs or otherwise. These needs include, but are not limited to, appropriate quantity and quality of food assistance, payment of full rent and utilities, payment of full rental deposits to landlord, daily necessities like cooking gas, clothing, health care, transport allowance for required trips always payable in full and in advance. We request that ISS-HK sign the Tenancy Agreements as refugees have no savings or income to pay rent balances every month.

We formally request that a public hearing be held to discuss these matters that concern all persons requesting and having been granted international protection in Hong Kong, who in March 2015 amounted to over 10,000 individuals, increasing by 300 every month.

Vision First further request that a Task Force be established to investigate why persons requesting and having been granted international protection in Hong Kong have been left destitute despite a system being in place to disburse government funding to prevent this condition from happening. Such policy failures have caused refugees needless and unreasonable physical, mental and psychological suffering.

Vision First invites refugees to download and complete the form below that will be filed at the Complaints Office of the Legislative Council Secretariat over the coming weeks and months.