Hong Kong requires a legal board in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre

Apr 30th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community | Comment

A year before the Unified Screening Mechanism was launched in March 2014, Vision First campaigned vigorously against Immigration Department’s apparently biased conduct and ostensible refusal to entertain CIDTP claims during the torture claim screening process. It is alarming that presently the problem is being repeated in relation to “Right to Life Claims.”

The rule of law in Hong Kong requires that every asylum claim be assessed with “anxious scrutiny and high standards of fairness” before Immigration exercises its statutory power of removal or deportation (CFA Prabakar case, Jun 2004) . This gives rise to an obligation to recognize the right not to be subject to torture, CIDTP and persecution for persons having no right to enter Hong Kong, including refugees detained in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) – some who have never been released on recognizance.

Backed by reports from claimants detained for prolonged periods, Vision First is concerned by the secretive nature of detention at CIC. The availability of publicly funded lawyers and interpreters at interviews in CIC is not a guarantee of high standards of fairness when refugees are denied second opinions and there is no legal board to offer advice to those in need.

A Middle Eastern refugee was detained over 8 months and resisted several attempts at removal. He reports, “Immigration refused to believe me. They forced me to the airport but I resisted. I knew my rights and demanded to be released to prove my case. Others who didn’t speak English were not as lucky as me.”

A refugee from India had his case rejected as he languished for 10 months in CIC. He recalls, “My lawyer told me to drop my claim and leave Hong Kong. He refused to help me with the appeal. I thought he was serving the interests of Immigration.”

In April 2015, Vision First met with the Hong Kong Bar Association to raise concerns about the respect of fundamental refugee rights in CIC detention. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Immigration is arbitrarily denying applications for “Right to Life” protection in the centre. There is a widely held belief that the zero percent acceptance rate reflects a strategy to deny protection despite the potential risk of life and limb for those expelled from Hong Kong.

Detainees would be alarmed to know that between 2009 and 2014 Immigration rejected 99.54% of 5581 claims determined. It is doubtful that any one of the 25 substantiated claimants was recognized inside CIC and released with protected status. Immigration should report how many claimants from which countries are detained at the airport, screened in detention and removed without being released on recognizance. What assurances can be made that they were treated fairly?

Hong Kong urgently requires a legal board to independently advise claimants in Immigration detention and prisons, monitor the implementation of asylum practices and ensure that the Unified Screening Mechanism pays more than lip service to high standards of fairness. Until that day comes it is suspected that the screening system lacks credibility, not refugees.

A month has passed since Vision First wrote an open letter to Immigration raising a series of questions in connection with Right to Life claims. Disappointingly no substantive reply was received from the Director of Immigration. In early April the Refugee Union established a 24-hour helpline for CIC detainees who can only make two local phone calls a month. The union has been contacted by dozens of refugees who appealed for independent legal assistance with asylum claims and lamented the treatment they received away from the public eye.

Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment?

Apr 20th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

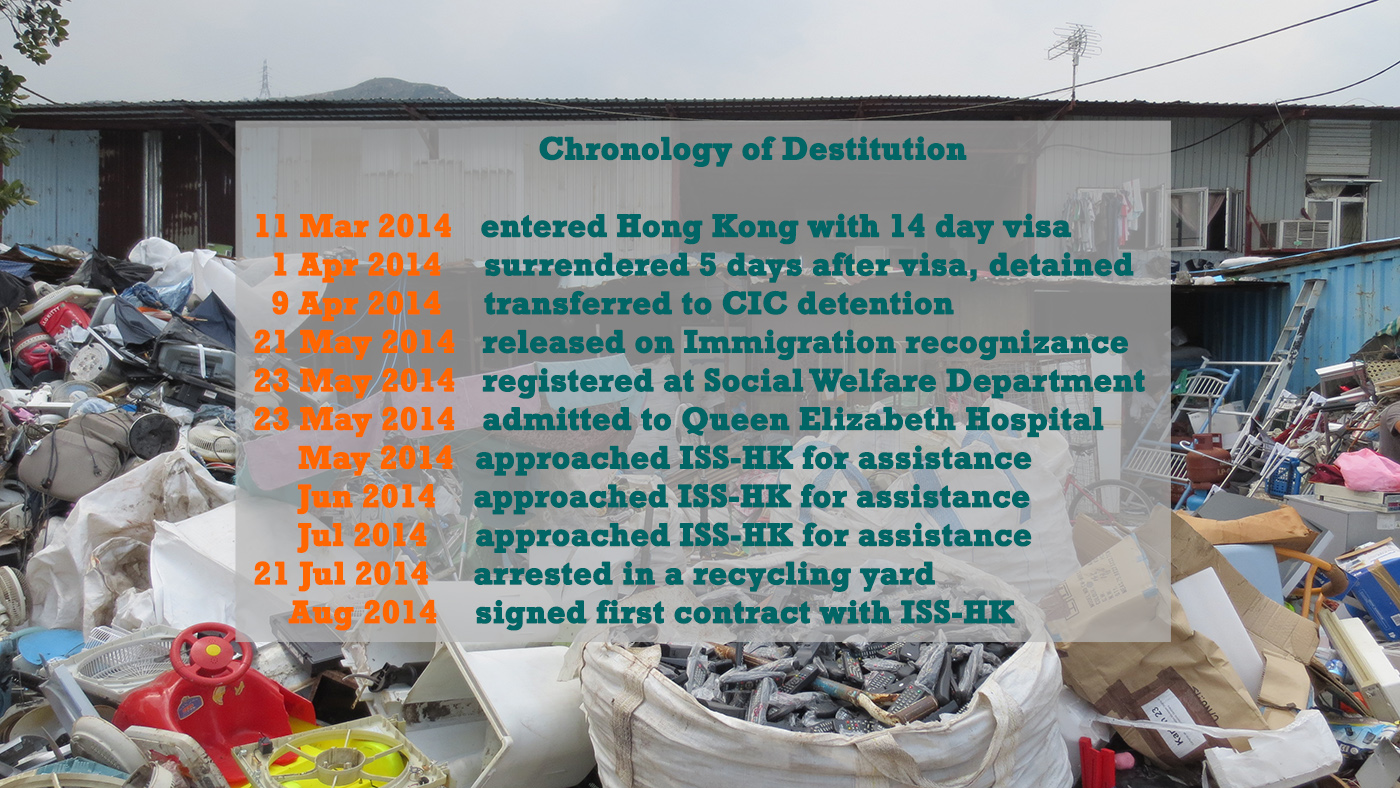

Called to the stand in Shatin Magistracy, Mohammed faced charges of breaching conditions of stay by taking up employment unlawfully. With the assistance of a Hindi interpreter, the despairing 50 year-old listened carefully before entering a plea – NOT GUILTY!

Asylum seekers are most commonly tarred with one brush. Public opinion is almost unanimous in accusing them of beating a path to our city to fraudulently drink in its riches by abusing welfare assistance, or toiling in the underground economy. Obfuscating the truth, the authorities regularly promote to the inattentive a rejection rate of 99.9% as evidence that only 1 in 1000 claims is meritorious.

The government remains unyielding and is adamant that the asylum mechanism offers genuine claimants a fair chance. No explanation is given about cases that have been pending for years often stretching to a decade. At the other end of the spectrum are recent arrivals who presumably didn’t expect to suffer like beggars after lodging protection claims with the Hong Kong Government.

Everything was better in Mohammed’s life before he took refuge in our city. If he didn’t face danger, he wouldn’t have left behind a supportive wife and adult children, abandoning a comfortable home and a thriving family business. At half a century of age, he hardly fits the stereotype of an adventurer seeking a better life in a developed country where illegal work might support remittances home.

One night, a few months after being released from Immigration detention, Mohammed regained consciousness in a ward at Queen Elizabeth Hospital. “I didn’t know how I got there. I was feeling ill that morning as I hadn’t had anything to eat and I was exhausted by sleeping outside week after week. The nurse told me that I had hit my head when I collapsed in the street. An ambulance was called and I was admitted to hospital for three days until I recovered.”

Holding back tears, he finds it hard to continue, “Those were the only three days when I ate properly since I was released from CIC. The nurses gave me extra food to make me stronger. For several months before I only ate what shops donated to me in Chung King Mansions. It was never enough. I lost a lot of weight and was often sick. I was worried when discharged from hospital as I knew I would be hungry.”

Mohammed reported that he had registered at the Social Welfare Department and had been referred to ISS-HK, but nobody called him for months. He forgets how long it was because several months passed in a blur of destitution, begging for handouts, sleeping in the streets, falling sick and depressed and always struggling with hunger. As if life couldn’t get more distressing, it did.

One Ramadan afternoon before the Zuhr prayers, he was accosted by a faithful at the Kowloon mosque who, presumably noticing his grime state, inquired about his condition. Mohammed explained that he was a refugee and had long run out of money and support. The well-wisher showed concern and with the enticement of a ‘breaking fast meal’ invited him on a trip in a private car to a recycling yard in Lok Ma Chau. The arrangement did not raise the suspicions of a newcomer in an international city.

Beggars can’t be choosers and nothing seemed out of the ordinary for hungry Mohammed about Muslim faithful offering desperately needed support in the name of Zakat – charity being one of the five pillars of Islam and a special obligation during Ramadan. Nobody suspected that police commandos were concealed in nearby bushes cocking machine guns to raid the isolated yard.

Around 3:30pm, before Mohammed enjoyed a single morsel of food, armed police burst inside. In the ensuing chaos, the panic-stricken refugee dove inside a wrecked car hugging the rusty floor until he was dragged out by the collar of his jacket two hours later, sweaty and confused. The fact that he was hiding from enforcement agents was subsequently put forward as evidence of his guilt.

Mohammed stands accused of working illegally. The police took photos of those arrested after the raid, not when they were allegedly working. The threadbare clothes of a homeless existence were put forward as work clothes, though Mohammed had arrived an hour earlier and his hands were clean.

It is certainly possible that Mohammed is lying and had accepted an offer for work at a time of acute desperation. Perhaps Mohammed is afraid of admitting the truth for fear of being jailed for 15 months for working illegally. Perhaps it wasn’t the first time he went to that yard and the police had failed to take such photo. But he claims to be innocent. And this arrest consequently raises more questions than answers.

How much of a crime is it to steal bread when you are hungry? How are refugees expected to survive for weeks and months before receiving welfare? For that matter, refugees are trapped between inadequate assistance and cope without breaking the law. Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment? In some jurisdiction offenders may be found innocent when authorities use deception to make arrests. Shouldn’t the courts take note of contextual evidence?

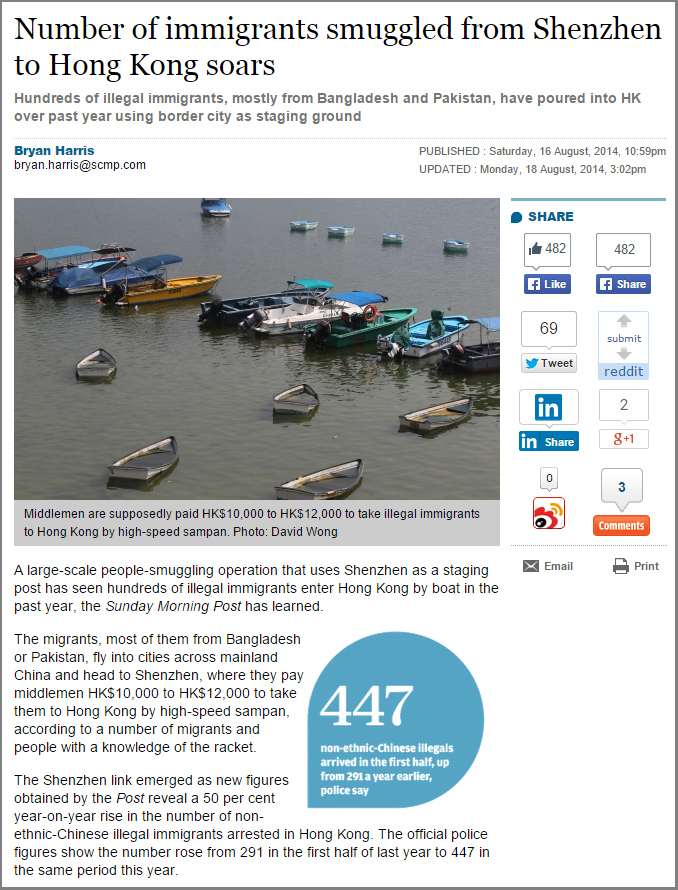

How many refugees enter illegally from China?

Apr 13th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion | Comment

“Our experience is that walls do not work … Walls can sometimes divert movement, but will not solve the problem”, said the UNHCR chief Mr. Guterres about the doubling of asylum seekers in Europe in 2014.

Hong Kong experienced a surge in the number of people claiming asylum, with 4,634 new cases lodged between March and December last year. Are these new asylum seekers also new arrivals? Have they been absconding for years and only recently came to know of this avenue of protection?

The CIA World Factbook puts Hong Kong’s land border at 30 km and its maritime border at 733 km, most of which is hard to penetrate undetected. We can only guess, but what is hardly a conjecture is that the controlled entrance points at the airport and land crossings are not the only passages into Hong Kong.

At a time when the authorities are targeting undesirable arrivals at the airport, nothing is said about the considerable number of refugees who enter illegally through other ways – some for the second or third time. It appears that the border with China is rather porous and, for the right price, the trip can be arranged with few hassles and no delay. The choices are various: through the fence, over the hills and by speedboats, known colloquially as ‘ferries’.

From many accounts collected by Vision First over the years, entering without a visa is not a matter of difficulty, but unsurprisingly only a question of money. In 2009 the going rate was 4,000 HK$, while today refugees are charged 12,000 to 15,000 HK$ per person.

Why is it so? Who is involved and who profits from this trade? Certainly it does not seem unreasonable, if the government is really worried about a trend that sees ever more requests for protection, to control what is now an extremely porous border. Or is it not a priority?

Here is the narrative of a refugee who recently arrived from Shenzhen that indicates the ease with which arrangements and journeys are made:

“I couldn’t get a visa with my same name so that is why I had to get illegal entry to Hong Kong. We applied for visa for China. It is not easy. I checked online. I checked with tourist agents. We made a tourist package and China sent us the information. We paid 238 USD per person in our group and they issued a letter that we took to the embassy in (our country).”

“Then we bought one-way air tickets to Guangzhou and stayed at a hotel booked online. The second day we took a train to Shenzhen … We didn’t get a stamp on our passport so we didn’t know how long we could stay in China. We waited there.”

“I asked [people] if there is any way to go from there to Hong Kong. A man gave me his mobile number. I used to talk to him every day. He kept telling me, ‘It is not ready. When it is ready I will let you know.’ He asked for 13,500 HKD each person … Every day I called him and asked when we can leave. He said the sea is dangerous, the cops can come there, so you must wait.”

“Almost one month later he suddenly called, ‘Today you must get ready’ … At 6pm we checked out of the hotel. We called a taxi. I called a Chinese guy who told the taxi driver where to go. I don’t know the location where the guy was waiting for us. He saw us and said, ‘You follow me’. I had never seen him before. We walked … then we stopped in a very dark place. He showed us a place on the water.”

“He told us to go sit (on the shore). There were stones in the shallow water and our feet got wet. Later several rowing boats arrived and took us. They rowed for a while and stopped under some trees, along the seashore. We waited longer. Then one of them took a torch and flicked the light a few times. Suddenly a motorboat appeared from the dark …”

“It was an outboard boat made of wood, about 3m long. It had a big engine. I was very scared. In my life it was the first time I had this experience. I was holding on and did not know what would happen. The driver said, ‘Keep still. Don’t move. Head down. Police there.’ He drove very fast …”

“Suddenly I saw my SIM card activated to Smartone, then I knew we were in Hong Kong. I ask him to stop us there as we were afraid and wanted to get off the boat. But he said, ‘No. Just sit there!’ He stopped further up by a small slope. He walked up and asked us to follow him. He called another man who was 20 meters away.”

“I feel that the border between China and Hong Kong is easy to cross. All the time I was praying in China on the bed because even my friends said it is not easy. I was afraid of crossing the sea, but these people made it very easy. Perhaps I was lucky because others say it is very dangerous …”

The other side of the domestic work-refugee nexus

Apr 10th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community, VF Opinion | Comment

There are two sides to the issue of foreign domestic workers falling pregnant and losing their jobs – one is local, the other overseas. On the home front, TVB recently reported on the plight of thousands of maids whose lives were disrupted by pregnancies that are not formulated into policies and, in some cases, are not respected by employers as workers’ rights.

There are some 320,000 foreign domestic helpers (FDH) who account for around 3 per cent of the Hong Kong population. The infamous case of Erwiana symbolised the risks of serious human and labour rights violation by devious employers who might treat maids as disposable slaves. By seemingly failing to enforce the law, the government is not making their plight easier.

Maternity protection is clearly a major concern for hundreds of thousands of female workers in prime child-bearing age. The Employment Ordinance is crystal clear: maids are eligible to 10 weeks’ paid maternity leave (after 40 weeks employment) and the dismissal of a pregnant worker is an offense. An employer who contravenes the provision is liable to prosecution and a fine of HK$ 100,000. But how many employers were successfully prosecuted?

The grim side of this story is that hundreds of pregnant maids seek asylum after being unjustly terminated, or falling out of employment The fear of departing Hong Kong should not be oversimplified. The fear matrix may include complex factors: income loss, illegal work, local partners, prior relationships, support networks, loan sharks, debt bondage, ostracization, religious prohibitions, family shame, customary expectations, racial discrimination and the threat of honour killing.

Contrary to popular belief, any person who overstays in Hong Kong may lodge a protection claim which ought to be approached on the premise that it is genuine until it is proven that it cannot be substantiated. Consequently no adverse inferences may be drawn against ex-maids (pregnant or not) since they might have legitimate claims and several have been recognized as refugees.

Our blog “Understanding the domestic work-refugee nexus” explained that maids are predictably drawn into the asylum sphere for several reasons. A crucial one is that they are not just workers, but are also women who endeavour to foster human relations in a society that diminishes their social worth and dehumanizes their femininity. It is natural that maids and refugees date because both communities are shunned by residents and are often deemed lesser human beings.

The distribution of thousands of boxes of Pampers (and condoms) at Vision First testifies to an escalating problem that the authorities are advised not to underestimate. The big picture is as predictable as it is problematic. Short of sterilization, Immigration has no way of curbing the sexual activity of 320,000 mostly female maids and 10,000 mostly male refugees who find comfort in each other’s arms. Is it surprising that these two communities meet and mingle?

Under the existing scheme, the government offers pregnant maids few choices but to return home under impoverished, unsafe circumstances, or seek asylum. Refugee fathers have little to offer their new families without work rights and adequate welfare assistance. The immigration status of the children follows that of the parents: if neither is a permanent resident, then the children are overstayers under the family’s or a parent’s claim.

The fear matrix becomes crucial. Once the asylum process is concluded, mothers ponder the pros and cons of returning home: Is the fear greater than the prospect of an immiserated existence? Is the danger of returning substantial, or could alternatives be explored given time? Nobody is under any illusion about the zero percent acceptance rate, but the variables are many and timing is key, because it is easier to return with a toddler than an infant. It would be advisable to allow mothers to work again rather than compel them to seek asylum as the only available pathway.

The government is concerned about the escalating cost (640 million HKD according to this report) of the asylum scheme. Priority should thus be given to formulating viable alternatives. Hong Kong society cannot enjoy the privilege of (underpaid) domestic workers without making provisions for natural consequences. We should not turn a blind eye to thousands of women whose rights are violated by policies that fail to envision maternity and its ramifications locally and overseas. Again Hong Kong is attempting to have its cake and eat it.

Immigration deploys heavy hand against pregnant woman

Mar 26th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Rejection | Comment

A 32 week pregnant former domestic worker reported to Vision First that in March 2015 Immigration officers used heavy-handed tactics in an attempt to remove her from Hong Kong International Airport.

Through sheer determination she scored a victory against state machinery that presumably safeguards border integrity with due regard to human rights.

Fitrini (not her real name), 28, was terminated by her Chinese employer when she was two months pregnant, despite discrimination against expectant women being outlawed in this cultured and sophisticated city. She recounts, “I read my contract and nothing said that I could not get pregnant. He didn’t have the right to terminate me. My agency said that they could not help.”

Fitrini fell pregnant with her South Asian boyfriend who supported her throughout the ordeal as they sought a way to stay together. They still plan to marry in the future, “after we find a solution to our problem because after my visa expired I had to leave Hong Kong.” They are in love and wish to raise their child together “if Immigration gave me a chance to stay here,” the mother explained.

In an attempt to stay legal, Fitrini went first to Macao for one month. Upon her return to Hong Kong she was questioned by Immigration and eventually granted a one week visa, “Because I said I have many clothes and things I must collect before I go back to my country.” She then left behind the city, her boyfriend and her dreams of a happy family.

Fitrini’s Muslim family was furious at her predicament. They felt that an unmarried pregnancy brought unforgivable shame to them. “My family could not accept me. Everyone turned against me because of the baby. I could not stay home, so I decided to return to Hong Kong. I hadn’t done anything wrong and thought that Immigration would give me a chance because my boyfriend was here.”

Fitrini narrated her experience. “I had a good record and I hoped Immigration would give me a visa upon arrival. Instead they refused me to let me in. They asked why I came back and I told them I had to meet my boyfriend. They detained me and warned, ‘This time no bargain’. I asked what does it mean? The said a flight had been arranged and I had to leave Hong Kong”

“I said I could not go back because I had problem with my family and I wanted to see my boyfriend, but they would not listen. [With a pretext] to move me to another office, they took me in front of the plane but I knew what it was and grabbed the cabinet and screamed. There were three female officers pulling me but I grabbed the chairs and screamed as many [passengers] watched.”

“I was 30 weeks pregnant and afraid to go back home. I have to stay in Hong Kong to see my boyfriend who was waiting outside the airport. Why they do that to me? They dragged me to the airplane three or four times and I have to fight with them … I was screaming and kicking in front of everyone. This was very shameful but I had no choice.”

“I did not tell them I understand Chinese. When they talked about getting a wheelchair and tying my arms and legs, I warned that I would make suicide before they put me on the plane. For four days they pressured me and used force. I did not believe that Hong Kong Immigration could do this. After four days they let me use my mobile phone and I called outside. Before they refused me to see the lawyer that came with my boyfriend, but then they agree.”

“I never wanted to be as a non-refoulement claimant, but I had to sign [a USM claim] to get in. I only wanted to see my boyfriend to find a way out for our problem. We have a baby and we want to be together. Immigration said I could not have the baby in Hong Kong. They force me to leave, but I fight with them and in the end they released me.”

This incident sheds light on questionable tactics adopted by Immigration officers to remove a vulnerable and pregnant Foreign Domestic Helper considered undesirable and deportable because no longer useful as cheap domestic labour, despite Hong Kong’s ostensible support of human rights.

Director of Immigration violating Refugee Constitutional Rights inside CIC

Mar 24th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Rejection, VF Report | Comment

Vision First is alarmed at news from detainees in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre, Tuen Mun (CIC). It is reported that the Director of Immigration may have failed to respect the importance placed on the non-derogable and absolute “Right to Life”, as enshrined in the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance that is binding on all government authorities.

On 23 March 2015, Vision First wrote an open letter to the Director of Immigration, inquiring among other issues about particulars of the training of officers charged with processing “Right to Life” claims. The Court of Final Appeal held that the right to freedom from being arbitrarily deprived of life also applied to persons not having the right to be in Hong Kong, including refugees.

The right not to be arbitrarily deprived of life (i.e. extra-judicially killed) is fundamental and absolute. It is a universal human right that cannot be limited, suspended or restricted for any reason, by any person.

Vision First is disturbed by allegations detailed in an email we received from a Refugee Union member who recently visited a detainee. Extracts from the email are as follows:

- CIC Immigration is doing really bad things. Just I come out from there after visiting my friend there;

- He says he already sent the BOR 2 claim form to Kowloon Bay but until now no results;

- There are many people inside who already applied for (High Court) Judicial Reviews (of Immigration Notices of Decision) 6 to 7 months before but still inside;

- In CIC immigration officers denied to accept BOR 2;

- People are inside very upset and afraid;

- They don’t understand what to do;

- They says that if they send letters to anyone those letters are not going out from CIC.

Several refugees confirmed this information. The Director of Immigration may be acting unlawfully in the execution of removal and deportation orders that ought to be stayed when detainees file “Right to Life” claims?

These allegations only deteriorate the already precarious reputation of the Hong Kong Government in the field of human rights, suggesting an ostensible turn towards uncompromising obstinacy that certainly stands at odds with the city’s self-proclaimed liberal and welcoming urban lifestyle.

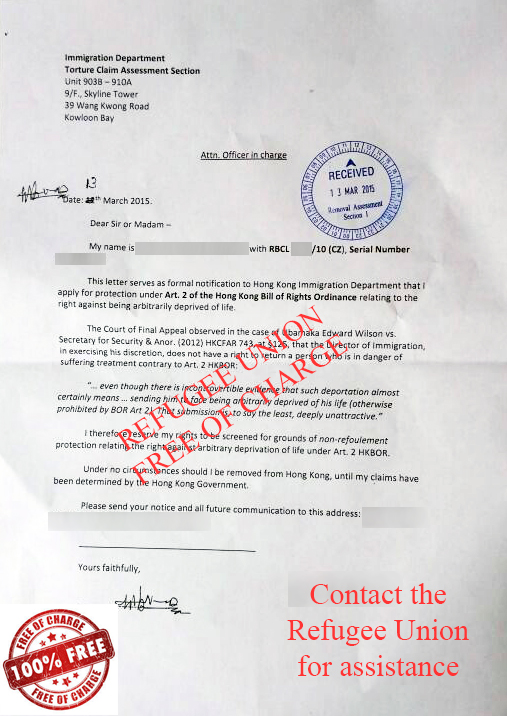

Vision First promotes “BOR 2 claim”

Mar 11th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, VF Opinion | Comment

Vision First reports that for almost a year some progressive legal professionals advised refugee clients to raise a “BOR 2 claim” together with their protection bids against torture, cruelty and persecution as prescribed under the Unified Screening Mechanism (USM).

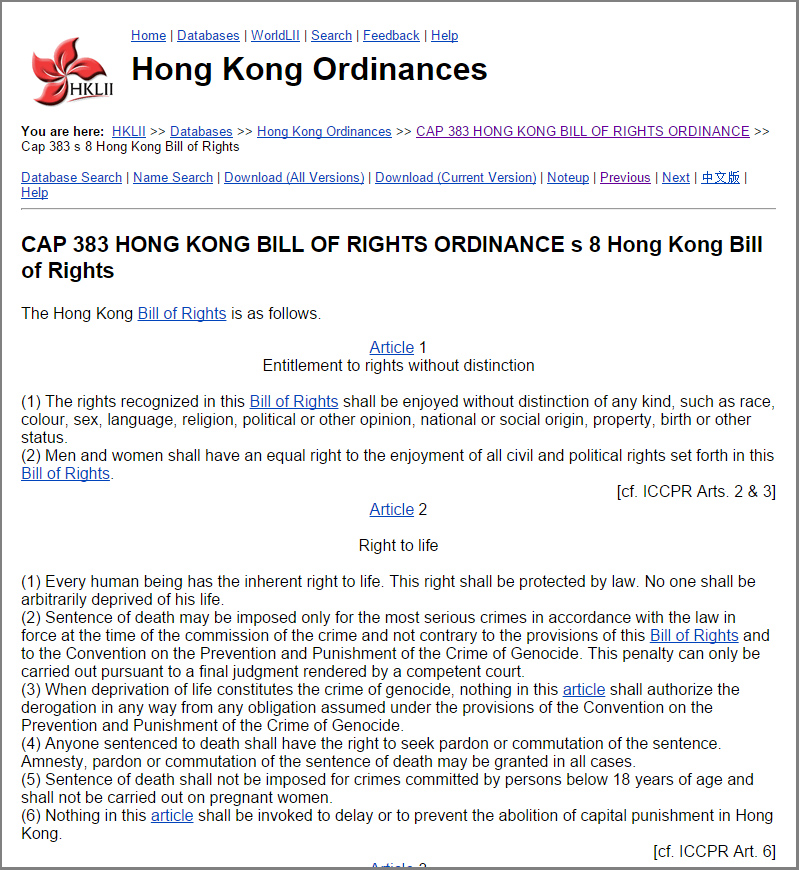

“BOR” is short for the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance (Cap 383), wherein Article 2 describes certain fundamental human rights: “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

HKBOR Article 2 (“BOR 2”) is a broad safeguard protecting the “right to life”. In brief, it defines that sentences of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes and ought to be carried out pursuant to a final judgment rendered by a competent court. Anyone sentenced to death shall have the right to seek pardon or commutation of the sentence.

Put simply, every human being has an inherent right to life which can only be forfeited in the administration of justice by a legitimate court that includes an appeal process. Amnesty of the sentence of death may be granted in all cases. It follows that no person can be unjustly killed, summarily executed, or fall victim to extra-judicial killing without legal proceedings.

The Hong Kong Bill of Rights is binding on all public authorities. In particular, the Court of Final Appeal found in the “Ubamaka judgment” (FACV 15/2011) that it may be unlawful for the Director of Immigration to exercise his discretion in favour of deporting refugees who might face arbitrary deprived of life – a deeply unattractive prospect contrary to article 2 of the Hong Kong Bill of Rights.

In light of USM having rejected 99.9% of claims in 2014, Vision First advises refugees to consider including the BOR 2 claim in their letters to Immigration raising asylum claims. By reserving the right to be screened for a risk of arbitrary deprivation of life, claimants have additional grounds of non-refoulement protection other than the three prescribed grounds.

Vision First reports that currently the Immigration Department will in most cases stay claims (whether at screening or decision stage) once claimants reserve the right to be assessed also for BOR 2. To date Immigration has not indicated in writing what their stance is regarding this new claim. This has the practical result of putting on hold such asylum claims until the USM is expanded to include an assessment for the arbitrary deprivation of life.

Consequently, the 826 refugees who had USM claims rejected at appeal in 2014 could theoretically lodge BOR 2 claims with the Immigration Department. It is reported that from 11 March 2015 detainees in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre will be permitted to file BOR 2 claims.

Book review: Asylum Seeking and the Global City

Mar 5th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration | Comment

Through the Karakorum to Hong Kong

Jan 2nd, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

I am Pakistani refugee and I arrived in Hong Kong in 2009 from Jehlum where my life was in mortal danger and police cannot help and protect me. I traveled along the Karakorum Highway, on the Silk Road, one of the wonders of the world, to a safe place because my family enemies want to kill me.

On my mind I have a question: Why do many people doubt the reason and way refugees come to Hong Kong? They doubt about this very much, so I will tell you my reason and my long trip along land from Islamabad to Hong Kong. I have never flown in an airplane in my life.

I was happy in my motherland Pakistan and I was having a good job running my own business. But after my father’s death, my other family members wanted to hold and take all our land and other property. At the time my father passed I was 18 years old. Over a few years the fighting get very worse and they killed my older brother and also want to kill me.

I was lucky to run away to another Islamabad to save my life, but they are strong and rich and find me there. I escape again and never feel my life is safe in Pakistan. In my country who have more money buy the police. Then the police refuse to protect victims who cannot pay more. They will also make false charges to arrest and put long time in jail those victims until they find money.

How did I know about refugees in HK and why I choose HK? I had some friends who were before here as refugees and they teach me how I can come, what documents I need and how much time and money it take. At that time I sell my business very cheap because hurry to get a passport with China visa.

I knew that I must reach Shenzhen (China) and that was my first target. I did not choose airplane because by road is much cheaper. I buy bus ticket from Islamabad to Gillgit, which is one and a half day drive. From there I take another bus to Sost, the Pakistan/China border which take more two days.

I buy again bus ticket from Sost to Kashgar (China) where I pass again immigration and they give me entry into China. But my target point is still very far because I need to reach Shenzhen, where Hong Kong is very near and I can easy enter. From Kashgar I buy train ticket to Urumqi, the big and old China city. Then I take a bus to Shanghai, another to Guangzhou and last one to Shenzhen.

I get a lot or problems in China all the way about food and language that is very different from my country. I reach Shenzhen at 11 o’clock at night and buy a SIM card for my mobile to contact my friend to ask him to please tell me how I enter Hong Kong because my visa is only for 23 days in China.

I stay in a hotel in Shenzhen because I am very tired as I was in train and bus for more than two weeks without rest as I carry on my journey. So the next morning my friend call me and tell me “You need to pay HK dollars 5500 for some men and they can help you to enter in Hong Kong by sea on a boat.” [In 2014 smugglers charged 14000 RMB for an illegal passage to Hong Kong]

At night the same day I meet the men near the Lo Wu McDonald and I pay them the money. They arrange for me a boat to take me to Hong Kong. They drive me in a small car to the seaside and a Chinese boy driver and other 8 people I see on the boat. It is 12 o’clock at night and the man go back in the car. I sit on the small boat that I worry it is very dangerous and only good to catch small fish.

After two hours already in the sea, some HK Marine Police boat come to us and tell us “Hands Up and show your identity!” It is very unlawful what I was doing, because without visa documents we can’t enter in any country, but I must find a safe place to save my life.

After I show my passport to the marine police, they say, “You are safe. Don’t worry!” and they bring me inside police station. From there they send me two days later to CIC detention center. I was bailed out in October 2009 and until today I am waiting to start my interview process.

(Name, Immigration and contact details provided)

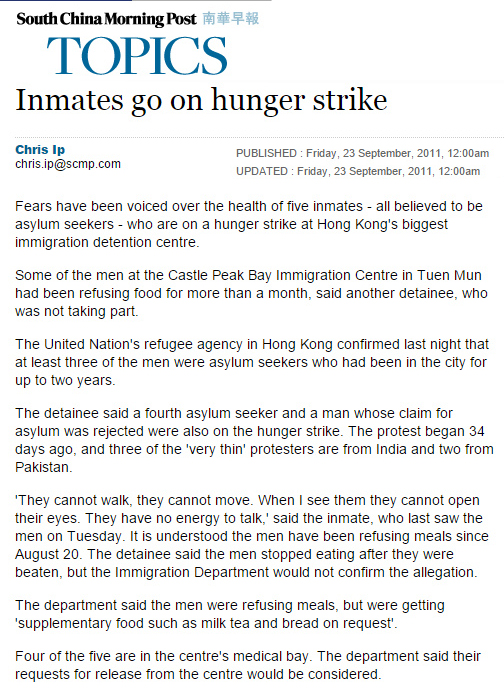

Hunger strike shows the face of death

Dec 22nd, 2014 | Detention, Immigration, Personal Experiences, Refugee Community | Comment

It was almost 15 years ago but I remember the day like it was yesterday. I came to Hong Kong to save my life. I had to find a safe place after fleeing Pakistan in the summer of 2001. After many years in 2010, my torture claim was rejected and I was charged with “remaining in Hong Kong unlawfully”. I was sent to prison for eight months for what I consider seeking asylum here.

When I was arrested, I was in shock … suddenly everything changed and I felt like a criminal. Immigration does not issue “asylum visas” so how are refugees expected to remain legally in Hong Kong while they wait for decision on their cases? Some refugees waited years for UNHCR to reject their case and didn’t surrender to Immigration. After rejection they were also prosecuted and jailed. Is it fair?

In June 2011 I was released from Pik Up Prison and transferred to Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (“CIC”) for deportation procedures. The government wanted to send me back to Pakistan where I told them my life was in serious danger. But nobody believed me. After I went inside CIC the office-in-charge took me to a room and shouted at me, “You must go back to your country!”

I said I would not go back, because my life is still not safe in Pakistan. After some questions, I had to sign some documents, then they sent me to the hall where a lot of people were waiting. Every day the officers force and force me to go back to my homeland. They didn’t’ listen. They didn’t believe. They didn’t understand. But why I choose more and more detention?

In this world, I think, most important and precious for every human being, after the air we breathe, is human rights and freedom. I always refused to be deported because I will face danger in Pakistan. Even if my arms and legs are bound in Hong Kong, I must prefer to stay here than return to be tortured to death.

When my trouble started we were 5 guys pressured by officers every day to leave Hong Kong. There were 2 Pakistani and 3 from India, but one India guy they sent back after a few weeks. And here I tell you a story that perhaps you will find hard to believe, but I have proof that I can show you. It was also reported in the South China Morning Post one day in September 2011.

The Immigration officers always force me to go back, but how I go back when still my problem is same since 2001? After many weeks the Immigration still refuse to give me bail out. I stopped eating and I was getting every day more and more sick. My hands and arms were shacking. They were not in my control. My arms were like rubber, they move and not stop. Then I was given a bed in prison hospital.

But Immigration still forced me to go back when I am sick. I was very tense. I was very scared. I didn’t know how many days or weeks I stopped eating. One night I went to toilet around 2am and I fell down. I could not stand up because my body was too weak already. My mind stopped working. Some friends helped to bring me out of the toilet. The officer-in-charge was shocked when he saw my condition.

The prison doctor called the emergency ambulance and they brought me out to Tuen Mun Hospital. I was in shock. I felt I was dreaming. The doctor injected me some medicine. After the check-up I was returned to prison hospital. I don’t know the exact date or month, but this happened during my detention at CIC, from 4 June 2011 to 20 June 2012. And they kept pressuring me to go back!

Later I learn the word “Hunger Strike”. For me it was just not eating as I wanted to die so the officers stop forcing me to go back my country. During the hunger strike three times my situation was very bad and I think I was dying. My body had no power. I don’t know how much weight I lost but my arms were skin and bones. My mind did not work and everything was like dreaming. Even my hands were not in control. Why I wanted to die and not live? I better loved detention and didn’t want to be deported. In prison I had life and breath and water. In my country I have fear and death. Why should I go back?

From childhood I read in books that for human life two things are most important: oxygen and water. So I had these two important things in my detention. More than 50 days I stayed inside the prison hospital. Many times they took me to Tuen Mun hospital. As a Muslim I believe in God and maybe I still have life because God is always with me.

I made 78 days hunger strike for my safety and for my freedom. Refugees who were inside with me are still in Hong Kong and they saw my arms become like sticks and my hands curl in like claws I could not move. I think the Merciful God gave me a new life and on 20 June 2012 Immigration give me bail out. Now even I forget my real birthday, because Immigration give me a new birthday.

So here in my mind I have a lot of questions. Was my long detention in CIC lawful? Were the law and the monthly notifications for further detention legal? The further detention made me hunger strike for 78 days. Even I was not a normal person, I was a prisoner. Even I had finished my sentenced in Pik Uk Prison. Even I was patient, but I could do nothing to make Immigration believe my case is real.

I stopped eating because I had no choice. If I go back I die suffering, but in prison I die peacefully. I stopped eating to try for freedom, to save my life. The law kept me in prison, but the hunger strike released me. The law is a very friendly thing for humanity. The country makes the law for a good and happy society. So we always try to do good and within the law. But every law is not always a right law.

I say respectfully that in my detention the law showed me the real face of death. I came very close to the world of death. Kindly believe me because every not eating day and hard suffering night, I saw the Main Gate of the Death World. But the good law cannot make me safe. The law make me dead. And luckily or unluckily I am writing to you about my detention time. And please I don’t want to be hurt more because of what I write now.

As human beings we must follow, accept and respect the law, but kindly I request that please you make the law with unity and humanity. And I hope that all the asylum seekers in Hong Kong and inside CIC detention will always follow the law. Even if we can make hunger strike for freedom, but we must do it peacefully and don’t break the law, because the law is the law.

(Name, Immigration number and contact provided)