Archive

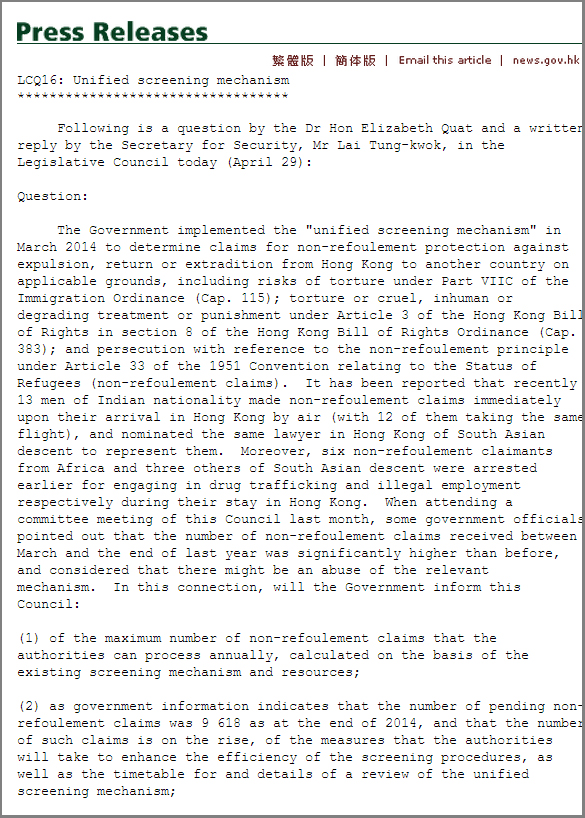

Security Bureau update on the Unified Screening Mechanism

Apr 30th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Government, Immigration, Legal | Comment

Hong Kong requires a legal board in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre

Apr 30th, 2015 | Detention, Immigration, Legal, Refugee Community | Comment

A year before the Unified Screening Mechanism was launched in March 2014, Vision First campaigned vigorously against Immigration Department’s apparently biased conduct and ostensible refusal to entertain CIDTP claims during the torture claim screening process. It is alarming that presently the problem is being repeated in relation to “Right to Life Claims.”

The rule of law in Hong Kong requires that every asylum claim be assessed with “anxious scrutiny and high standards of fairness” before Immigration exercises its statutory power of removal or deportation (CFA Prabakar case, Jun 2004) . This gives rise to an obligation to recognize the right not to be subject to torture, CIDTP and persecution for persons having no right to enter Hong Kong, including refugees detained in Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) – some who have never been released on recognizance.

Backed by reports from claimants detained for prolonged periods, Vision First is concerned by the secretive nature of detention at CIC. The availability of publicly funded lawyers and interpreters at interviews in CIC is not a guarantee of high standards of fairness when refugees are denied second opinions and there is no legal board to offer advice to those in need.

A Middle Eastern refugee was detained over 8 months and resisted several attempts at removal. He reports, “Immigration refused to believe me. They forced me to the airport but I resisted. I knew my rights and demanded to be released to prove my case. Others who didn’t speak English were not as lucky as me.”

A refugee from India had his case rejected as he languished for 10 months in CIC. He recalls, “My lawyer told me to drop my claim and leave Hong Kong. He refused to help me with the appeal. I thought he was serving the interests of Immigration.”

In April 2015, Vision First met with the Hong Kong Bar Association to raise concerns about the respect of fundamental refugee rights in CIC detention. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Immigration is arbitrarily denying applications for “Right to Life” protection in the centre. There is a widely held belief that the zero percent acceptance rate reflects a strategy to deny protection despite the potential risk of life and limb for those expelled from Hong Kong.

Detainees would be alarmed to know that between 2009 and 2014 Immigration rejected 99.54% of 5581 claims determined. It is doubtful that any one of the 25 substantiated claimants was recognized inside CIC and released with protected status. Immigration should report how many claimants from which countries are detained at the airport, screened in detention and removed without being released on recognizance. What assurances can be made that they were treated fairly?

Hong Kong urgently requires a legal board to independently advise claimants in Immigration detention and prisons, monitor the implementation of asylum practices and ensure that the Unified Screening Mechanism pays more than lip service to high standards of fairness. Until that day comes it is suspected that the screening system lacks credibility, not refugees.

A month has passed since Vision First wrote an open letter to Immigration raising a series of questions in connection with Right to Life claims. Disappointingly no substantive reply was received from the Director of Immigration. In early April the Refugee Union established a 24-hour helpline for CIC detainees who can only make two local phone calls a month. The union has been contacted by dozens of refugees who appealed for independent legal assistance with asylum claims and lamented the treatment they received away from the public eye.

‘Citizenfour’ Director Laura Poitras on Snowden, John Oliver & Guarding Your Privacy

Apr 30th, 2015 | VF Team | Comment

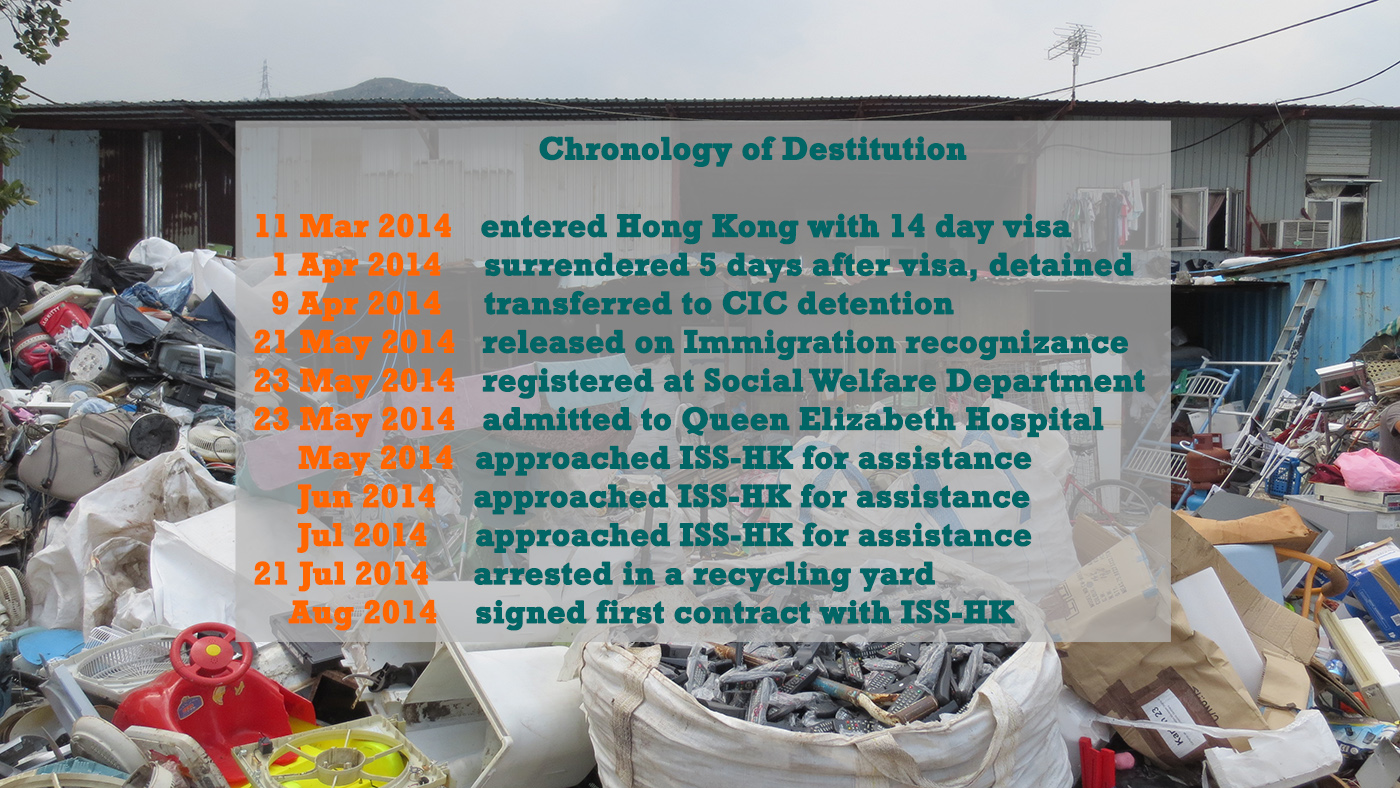

True protection eludes a recognized refugee

Apr 29th, 2015 | Immigration, Medical, Personal Experiences, Rejection, VF Report | Comment

After five years of deep emotional and economic suffering in Hong Kong, on 15 January 2015 Ali was rushed to the hospital with pain in his chest. He recalls, “The medical officer informed me that one of my heart vessels is blocked. They (need to perform an) angioplasty to fix a stent in the blocked vain. But I have to pay 20,000 HK$ myself as the stent is not available from the hospital (free for refugees). I told him that due to my status, it is not possible for me to pay such a huge amount … ISS case worker and UNHCR said sorry that we do not have funds for that purpose.”

Who is Ali? Ali is a 62 year-old recognized refugee from Pakistan in Hong Kong since January 2010. He spent several winters freezing in a container abandoned in a Kam Tin recycling yard. In the summer his home became unbearably hot. Before rental deposits were introduced for refugees, Ali accepted such limited hospitality from residents offering temporary shelter. By living in a possible illegal work place, the Pakistani defied the common assumption that his countrymen abused asylum to work in Hong Kong.

For five years, Vision First followed closely Ali’s asylum experiences in our inhospitable city.

Ali feels betrayed by Hong Kong’s promises of protection, “In January 2010 I left my country, business, mother, wife, children, brothers, sisters, friends and relatives hoping that Hong Kong Government and UNHCR will appreciate our sacrifices in the war against terrorism by opening their hearts and help us in standing again on our feet. But all our expectations were ruined by the different functionaries of the government and UNHCR.”

In May 2011 the Immigration Department rejected Ali’s torture claim at appeal. He was stoically terse, “It is a childish decision!” The rejection by UNHCR in December 2012 was traumatizing, as it crushed his trust in the international agency. When Legal Aid rejected his application to judicially review his CAT rejection, the disheartened family man hit rock bottom. Sick and depressed, Ali seemed on the verge of giving up more than his bid for asylum. In those dark days, only family thoughts kept him going, “I have many burdens with my family. How can I help them? The whole family is looking to me. They are stuck. They want to know when they can come and join me.”

Conspiracists might be forgiven for speculating about the baffling backpedaling by UNHCR which unexpectedly confirmed his status as a refugee on 29 April 2014. It might not be a coincidence that Ali’s lawyers had reversed the Legal Aid decision and prepared a well-document, arguable case that might have forced Immigration to reconsider its decision. Ali suspects that the government put pressure on UNHCR to resolve his claim and stop legal proceedings.

At the time he was hospitalized, Ali was informed that since his condition had not reached a ‘life threatening state’, the hospital could not proceed with free surgery and he would have to pay for the stent himself. Five years in limbo without the right to work dilapidated Ali personal resources. Today he is truly destitute. ISS-HK referred him to SWD which unempathically stated that they would not pay until his condition deteriorated.

Let’s face it. Ali has been treated poorly from the day he arrived and was reduced to living in a shipping container for years. His family was displaced and fell from relative prosperity to grim poverty. Now Ali spends the days bedridden in a room that appears to be an illegal structure. He is afraid his heart will fail overnight. He hardly dares to walk outside for fear of collapsing in the street, which ironically might be the only chance he has to receive the necessary surgery.

Hospitals, ISS-HK and SWD kick away responsibility like a ball. Is it reasonable to ask a sick refugee to raise money himself to save his life despite being granted international protection? What meaning does the status of refugee carry for UNHCR, ISS-HK, SWD and the government? Who will be held accountable in a worst case scenario for such absurd conditions of institutional punitive confinement? Hong Kong should step up and honor Ali’s protection with the peace of mind and wellbeing it ought to entail.

Welfare punishment is a doubtful deterrent

Apr 27th, 2015 | Crime, Housing, Legal, VF Report, Welfare | Comment

The Hong Kong government has a preference to describe asylum in negative terms: “Non-refoulement claimants in Hong Kong are illegal immigrants or overstayers, even if their claim is substantiated … they may not take up employment in Hong Kong; violation of the relevant provisions is a criminal offence punishable on conviction to a fine of up to level 5 ($50,000) or to imprisonment for three years … the sentencing guideline in respect of the relevant provision states that 15 months’ imprisonment should be imposed on a person convicted of an offence.” (Finance Committee 2015-16)

Very few lawyers stand apart for attaching the utmost importance to refugee rights and striving to ensure such rights are respected and safeguarded in the interest of the asylum community and the city’s reputation. The reality is that in most cases they have to represent clients pro bono.

In February 2014, barrister Robert Tibbo obtained leave to make an application for the judicial review of the torture claim of a South Asian woman whose appeal was dismissed without an oral hearing. Her council, a non-executive director of Vision First, argued that various factual matters relevant to the case had not been addressed by the adjudicator who cherry-picked country of origin information.

The woman sought refuge in Hong Kong in 2005 to escape from threats to her life and safety due to her political activities and the serious abuse she received from her husband affiliated to an opposing political party. As if her struggle for protection was not enough, a decade later she stood before the bench in Eastern Magistracy to answer to charges of working illegally.

In 2013, the woman was arrested by police at the back of a restaurant where she occasionally washed dishes for exploitative wages. For months she had paid cash for a dilapidated subdivided room, because the landlord refused to accept bank transfers from ISS-HK and she was unable to find alternative accommodation within the paltry rental budget that was then 1200 HK$.

It is not uncommon for refugees to rent the cheapest rooms from landlords who prefer cash payments to reporting bank transaction in income statements. In such cases tenants are obliged to secure cash somehow, or risk being homeless. Under the circumstances, the great majority of refugees seek employment in the informal economy and risk arrest, prosecution and jail for attempting to make ends meet.

Interestingly this woman’s situation ticks several failures in the current asylum policy: 1) denial of protection; 2) prolonged determination of claims; 3) prohibition from working, and 4) insufficient welfare assistance, which in this case included failure by ISS-HK to secure suitable accommodation for a vulnerable woman. Robert Tibbo is seeking a stay of prosecution arguing that systemic failures placed his client in a predicament in which she worked to avoid sleeping in the street.

At a hearing in April 2015, the magistrate suggested that a judicial review be sought against the Director of Immigration who sets the recognizance conditions, including the prohibition from taking up employment. The argument is that if the government openly met the basic needs of refugees and signed tenancy agreements, then refugees would not be compelled to work illegally.

Robert Tibbo explains, “This case is likely to go to the Court of Final Appeal. It is hardly unique since countless refugees struggle daily to pay necessary costs not met by ISS-HK. My client is a victim of an intentional failure by the Government to meet the basic needs of refugees who, when facing similar charges, often plead guilty to avoid stiffer sentences while cognizance that they were entrapped. This case has the potential of changing the system.”

A legal and moral obligation to increase welfare to realistic levels

Apr 23rd, 2015 | Housing, Immigration, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

Refugees in Hong Kong worry most about two issues: protection and welfare. Over the years the Immigration Department has done little to allay suspicions that the effective zero-percent acceptance rate is a poor assessment of the asylum community. Welfare issues are equally troubling with policies that deliberately entrap refugees below the poverty line without employment rights.

On a scale of importance, Vision First is primarily concerned about the failure of the Unified Screening Mechanism to generate protection. In the interest of accountability and transparency, Immigration ought to publish monthly results to inform interested parties about its accomplishments in the asylum sphere. This would undoubtedly better inform opinions.

After Hong Kong’s top court denied the right to work in February 2014 to mandated refugees and successful torture claimants, it became disappointingly clear that the authorities are years away from granting employment rights to asylum seekers condemned, by policy and design, to a protracted state of emotional and economic destitution with deterrence aims.

A combination of questionable policies force refugees to run the gauntlet between insufficient welfare and imprisonment for working illegally. Such arrangements strike offenders heavily with arrests and imprisonment that are hardly avoidable when money must be regularly raised to meet necessary expenses, such as rent surpluses, utilities, food and clothing.

Instigated by superficial media reporting, common perception assumes that refugees should receive less welfare than impoverished residents. This is shamefully reflected in the welfare disparity between citizens and refugees, despite the former being allowed to work and the latter jailed up to 22 months for breaking the law in a hostile, and arguably unjust environment.

On 22 April 2015, Vision First and the Refugee Union met with the Hon. Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung to strategize on increasing welfare levels that are unrealistically low (HK$ 1500 for rent and HK$ 1200 for food) and have fallen behind inflection, particularly in the rental market. A first batch of 300 complaint forms were submitted to the Legislative Council’s Redress System to trigger a discussion by the Panel on Welfare that advises the government on such matters.

Questions will be raised about the adequacy of the current assistance which fail to meet the basic needs of a growing refugee population. Deterrence objectives and criminalization of vulnerable foreigners should not overshadow welfare considerations when men, women and children are suffering in our community. As long as work rights are denied, the authorities have a legal and moral obligation to increase welfare to realistic levels consistent with human right laws.

The cardboard box community of Sham Shui Po

Apr 21st, 2015 | Advocacy, Housing, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

A fire broke out on a remarkable foot bridge over four-lane Yen Chow Street West in Sham Shui Po on the night of 19 April 2015. This pedestrian crossings was home to over a dozen homeless persons who lived in semi-permanent huts made of plywood, cardboard and plastic sheets. Some had lived there for years.

News of the fire spread quickly among refugees who three times a month join a local charity, which prefers to remain anonymous, to distribute food to this homeless community comprising mostly elderly and troubled residents. This humanitarian service has brought refugees closer to impoverished residents who suffer similar neglect and deprivation in our affluent city.

While firefighters doused the flames, several concern groups rushed to offer assistance and speak about the shameful conditions endured by several hundred vulnerable persons in the neighbourhood. A Refugee Union member later observed, “NGO people should coordinate efforts to advocate for badly needed changes … better welfare and proper homes is what these people need … Isn’t the government ashamed how people suffer in the streets?”

After the fire, a passive-reactive government did what it does best – lock the stable doors after the horse has bolted. Drawing parallels with the fires that brought death and destruction to refugee slums, the Fire Service Department clamped down on the homeless people living on that food bridge with little concern where they would end up sleeping – possibly under a different flyover.

An NGO worker familiar with the area reported that there are over 60 Vietnamese refugees living in cardboard huts under that section of the West Kowloon Corridor. A long row of huts adjacent to the Tung Chau Street Park offers a sheltered space for sleeping and storage. These shacks are apparently tolerated by the authorities on the hidden side of the wet market where they are less likely to offend the public conscience.

It is understood that the refugees living there collect groceries at the ISS-HK appointed shops and cook with gas stoves on the pavement. There is no electricity for refrigerators. These refugees are unable to rent rooms for the 1500$ allowance and lack the organizational skills to request better assistance. They might strengthen statistics presented to the Social Welfare Department that encompass refugees who collect food rations, but seemingly do not require rent assistance.

Vision First will partner with Refugee Union to plan a Vietnamese language drive to reach out to this most marginalized and uninformed sub-group said to comprise veterans who have been in Hong Kong for twenty years as well as newcomers who arrived within the last year.

The plight of the homeless ought to be a concern for all citizens privileged to sleep under a proper roof. The human suffering caused by ineffective policies ought to resonate with everyone as we wonder why government and community are failing the most vulnerable in society, citizens and foreigners alike.

“Tonight we will gather to serve the homeless again,” remarked a refugee mother, “There are people suffering worse than us and this (community service) opened my eyes. I cannot work, but I can help other needy people. This is very meaningful for me. At the end of the day we are the suffering people … It doesn’t matter the colour of our skin or where we come from.”

Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment?

Apr 20th, 2015 | Crime, Detention, Immigration, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

Called to the stand in Shatin Magistracy, Mohammed faced charges of breaching conditions of stay by taking up employment unlawfully. With the assistance of a Hindi interpreter, the despairing 50 year-old listened carefully before entering a plea – NOT GUILTY!

Asylum seekers are most commonly tarred with one brush. Public opinion is almost unanimous in accusing them of beating a path to our city to fraudulently drink in its riches by abusing welfare assistance, or toiling in the underground economy. Obfuscating the truth, the authorities regularly promote to the inattentive a rejection rate of 99.9% as evidence that only 1 in 1000 claims is meritorious.

The government remains unyielding and is adamant that the asylum mechanism offers genuine claimants a fair chance. No explanation is given about cases that have been pending for years often stretching to a decade. At the other end of the spectrum are recent arrivals who presumably didn’t expect to suffer like beggars after lodging protection claims with the Hong Kong Government.

Everything was better in Mohammed’s life before he took refuge in our city. If he didn’t face danger, he wouldn’t have left behind a supportive wife and adult children, abandoning a comfortable home and a thriving family business. At half a century of age, he hardly fits the stereotype of an adventurer seeking a better life in a developed country where illegal work might support remittances home.

One night, a few months after being released from Immigration detention, Mohammed regained consciousness in a ward at Queen Elizabeth Hospital. “I didn’t know how I got there. I was feeling ill that morning as I hadn’t had anything to eat and I was exhausted by sleeping outside week after week. The nurse told me that I had hit my head when I collapsed in the street. An ambulance was called and I was admitted to hospital for three days until I recovered.”

Holding back tears, he finds it hard to continue, “Those were the only three days when I ate properly since I was released from CIC. The nurses gave me extra food to make me stronger. For several months before I only ate what shops donated to me in Chung King Mansions. It was never enough. I lost a lot of weight and was often sick. I was worried when discharged from hospital as I knew I would be hungry.”

Mohammed reported that he had registered at the Social Welfare Department and had been referred to ISS-HK, but nobody called him for months. He forgets how long it was because several months passed in a blur of destitution, begging for handouts, sleeping in the streets, falling sick and depressed and always struggling with hunger. As if life couldn’t get more distressing, it did.

One Ramadan afternoon before the Zuhr prayers, he was accosted by a faithful at the Kowloon mosque who, presumably noticing his grime state, inquired about his condition. Mohammed explained that he was a refugee and had long run out of money and support. The well-wisher showed concern and with the enticement of a ‘breaking fast meal’ invited him on a trip in a private car to a recycling yard in Lok Ma Chau. The arrangement did not raise the suspicions of a newcomer in an international city.

Beggars can’t be choosers and nothing seemed out of the ordinary for hungry Mohammed about Muslim faithful offering desperately needed support in the name of Zakat – charity being one of the five pillars of Islam and a special obligation during Ramadan. Nobody suspected that police commandos were concealed in nearby bushes cocking machine guns to raid the isolated yard.

Around 3:30pm, before Mohammed enjoyed a single morsel of food, armed police burst inside. In the ensuing chaos, the panic-stricken refugee dove inside a wrecked car hugging the rusty floor until he was dragged out by the collar of his jacket two hours later, sweaty and confused. The fact that he was hiding from enforcement agents was subsequently put forward as evidence of his guilt.

Mohammed stands accused of working illegally. The police took photos of those arrested after the raid, not when they were allegedly working. The threadbare clothes of a homeless existence were put forward as work clothes, though Mohammed had arrived an hour earlier and his hands were clean.

It is certainly possible that Mohammed is lying and had accepted an offer for work at a time of acute desperation. Perhaps Mohammed is afraid of admitting the truth for fear of being jailed for 15 months for working illegally. Perhaps it wasn’t the first time he went to that yard and the police had failed to take such photo. But he claims to be innocent. And this arrest consequently raises more questions than answers.

How much of a crime is it to steal bread when you are hungry? How are refugees expected to survive for weeks and months before receiving welfare? For that matter, refugees are trapped between inadequate assistance and cope without breaking the law. Is the government promoting “no welfare – no work” entrapment? In some jurisdiction offenders may be found innocent when authorities use deception to make arrests. Shouldn’t the courts take note of contextual evidence?

HKU Magazine – 遠走他方的故事

Apr 15th, 2015 | Advocacy, Immigration, Media, Refugee Community | Comment

遠走他方的故事

Residual welfare is formulated to entrap refugees

Apr 15th, 2015 | Crime, VF Opinion, Welfare | Comment

In pre-industrial, agrarian society the needs of the vulnerable were generally met by family, kinship provisions, neighbourhood, informal support networks, religious institution and the charity of the rich based on normative values of empathy, mutual help, locality ties and religious beliefs. The state offered no institutional assistance.

In modern times, these informal arrangements were admirably taken over by the state in the interest of “those who are not capable without help and support of standing on their own feet as fully independent or self-directing members of the community”. It was understood that “welfare addresses social needs accepted as essential to the well-being of a society. It focuses on personal and social problems, both existing and potential.” (HK Gov 1965 + 1991 White Papers).

Nonetheless, with 1.5 million citizens living in poverty, and thousands more struggling to afford three square meals a day, the Hong Kong welfare model is often considered an embarrassment. The administration falls short of fully mobilizing its considerable resources to alleviate the emotional and economic suffering of its most vulnerable citizens.

In reality, scholars tend to see local welfare as a residual system. That is welfare that only partly ameliorates the failures of the market economy, precisely because the privileges of the rich in society should not be undermined by a burdening tax system that is claimed would inevitably become needed were more services needed by larger numbers of welfare claimants.

After decades neglecting refugees, the government provided welfare in 2006. But the authorities persistently reiterate the service is “to prevent destitution while not creating a magnet effect which may have serious implications for the sustainability of our current support systems and for our immigration control.” In other words, this is another form of residual welfare.

But here is the catch. Uprooted from family, kinship and locality ties, refugees in Hong Kong are displaced and deficiently assisted by support networks, institutional services and charitable organizations. The assistance levels provided by the government condemn them to dire poverty that is compounded by the denial of work rights and 15 months imprisonment for those arrested working.

As opposed to a solidarity model based on principles of mutual responsibility, a residual welfare model offers a partial safety net confined to those who are unable to manage otherwise, with the assumption that they are able to locate further sources of assistance on their own. This notion then suggests that 10,000 refugees in Hong Kong ought to supplement inadequate government assistance through hand-outs from family, countrymen, neighbours, religious institutions and NGOs … or by working illegally.

Policies directed against the poor have to do with the government abdicating its duty to alleviate distress and poverty, as much as with crafting a hostile environment in which an undesirable foreign class adapts by resorting to all sorts of social tricks and risking arrest for doing something illegal because they have no choice. A case in point is a refugee who already has 5 convictions for theft. He candidly explains, “I steal baby formula because easy to sell. If police arrest me I go prison 2 to 3 months. If I am arrested working I will go prison for 2 years because of prior convictions.”

The expectation of self-reliance from refugees who frequently don’t know a soul in town is absurd. They report the absurdity of the residual welfare system through suggestions commonly made by their case workers:

– “You must wait 2 to 3 months before we start the assistance.”

– “We cannot help you. You must find the money yourself.”

– “You should ask some NGO to pay for or donate what you need.”

– “You should ask your friends to help you pay for it.”

– “You should find some church to assist you.”

– “This is not our problem. You must manage by yourself.”